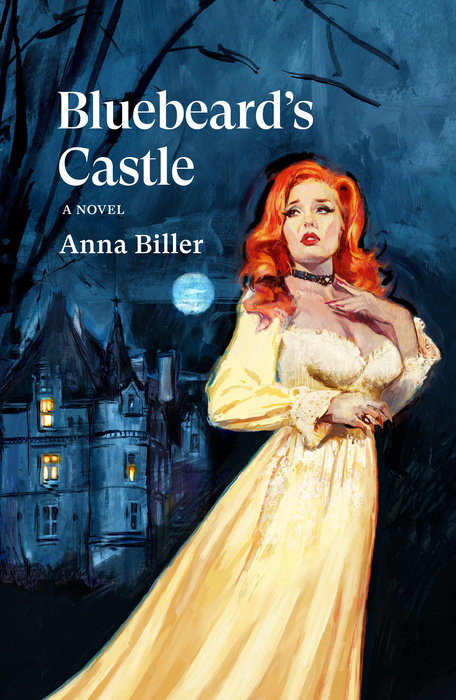

FILMMAKER ANNA BILLER begins her debut novel, Bluebeard’s Castle, with a warning: “Some husbands,” she writes, “are pussycats, some are dullards or harmless rogues, and some are Bluebeards.” Folklore and literary history are full of Bluebeards: Charles Perrault’s original fairy tale, two Brothers Grimm versions, Jane Eyre’s Mr. Rochester, modern retellings by writers, composers, and directors ranging from Georges Méliès and Béla Bartók to Helen Oyeyemi and Catherine Breillat. The elements of the story remain essentially the same: a young woman marries a mysterious, wealthy widower. Despite warnings (sometimes from her husband, sometimes from outsiders), she explores the recesses of his house and discovers that he has murdered all his former wives and keeps their bodies in a hidden chamber. The intrepid bride eventually reveals his secret, and the monster is punished—hacked to bits or burned alive. Though the story often has fantastic aspects—a talking bird, people who miraculously come back to life when their dismembered parts are reunited, a magical key or egg that proves that the wife found the chamber—true anxiety lies at its heart. Marriage is a gamble, it reminds us, and any husband could turn out to be a wife-killer.

Perrault’s 1697 version ends with two alarming morals, despite his heroine’s triumphant escape. The first pins the blame on the bride, opining that women too easily succumb to the “fleeting pleasures” of curiosity, which “always prov[e] very, very costly.” The placatory second suggests that readers need not fear, for in the seventeenth century, “No longer are husbands so terrible” and “with their wives they toe the line.” With Bluebeard’s Castle, Biller vehemently disagrees with both glosses of the original story. There is a reason we can’t shake off Bluebeard, the book asserts: victim-blaming and femicide are as relevant now as they were in Perrault’s day. The primal fear of the murderous husband that generated so many Bluebeard retellings is with us still—in sensational ways, as in the true crime entertainment business, but also, as Biller highlights, in the very real fear of being trapped in an abusive relationship. Twenty-first-century readers may have a new vocabulary for, and theoretical understanding of, intimate partner violence, but no amount of pop psychology—or serious analysis, for that matter—has yet been able to prevent it from happening.

Bluebeard’s Castle takes on the challenge of reframing an oft-told tale in the context of modern-day beliefs and lingering misconceptions about domestic abuse. We meet our heroine, Judith, as she is mulling over the ample evidence that her husband, Gavin, plans to murder her. “Was it all in her head?” she asks. “Like many young women she tended to imagine the worst about men, and sometimes she blew her fears out of proportion.” The novel then backtracks to trace the relationship from start to finish, as aristocratic romance novelist Judith falls under the malevolent spell of Gavin, a gold-digging fantasist. He “love-bombed her to within an inch of her life” and Judith transforms from “a plain, unhappy, bookish girl into a beautiful romance heroine, practically overnight,” before Gavin reveals his true nature.

From the first page, we know that Judith must leave, but the bulk of the novel is a back-and-forth between her repeated attempts to flee and the pernicious enthrallment to Gavin that compels her to stay. Judith is well versed in the workings of toxic relationships, which she explains early on when her clueless brother-in-law asks why “you ladies end up with sociopaths.” “Sociopaths are very good at love-bombing and gaslighting their victims,” she states, informing him that “anyone can fall for a sociopath. Anyone.” Including, Judith soon recognizes, herself. For confirmation, she refers to a bookmarked passage in “a well-worn book” from her library, Bad Men and the Women Who Love Them. In Biller’s hands, fascination with the unknown—the unfathomable darkness of Bluebeard himself—and the fatal curiosity it inspires are tied into the mystery of why a woman might stay with a monster. “Love is madness,” Judith declares at one point, unwittingly describing her own situation, “no one can really understand it except the person who suffers it.”

Yet how to let readers in on this madness? As in her films, here Biller deploys the conventions of a given genre—in this case, the gothic romance novels that Judith reads and writes—in order to subvert them. Reflecting on the art that inspires her in a recent interview, Biller said: “You have something that’s within a structure of pleasure—visual pleasure, narrative pleasure—and then there’s a moral tale embedded within it.” Biller’s 2016 film, The Love Witch, fits this description. Styled and structured like a 1960s B movie, Biller’s immaculately precise tribute to the genre is initially intoxicating, what with its gorgeous artifice and arch humor, but viewers are ultimately left to ponder the obsession with heterosexual romance that leaves its heroine blood-spattered and alone (albeit perfectly coiffed, turquoise eyeshadow unsmudged). What seems at first like a deliciously indulgent homage to the period slyly critiques its values, while still encouraging the audience to enjoy its titillations.

Bluebeard’s Castle attempts to pull off a similar coup, relying on tropes from various points in the gothic novel’s long history to sweep readers off their feet and transport them to “both the depths of debauchery and the heights of ecstasy” as Gavin does to Judith, before revealing the insidious dangers within. Biller plays with the stylings of the eighteenth-century gothic (the origin of so many of our threadbare images of ruined castles, stormy nights, and chain-rattling ghosts), the Brontës’ nineteenth-century psychodrama, Daphne du Maurier’s glamorous mid-century melancholy, and the melodrama of the bodice-ripper romance. That Biller is consciously mashing literary historical references together is evident in the name of Judith and Gavin’s castle: Manderfield, an awkward chimera of Manderley, the setting of Du Maurier’s Rebecca, and Thornfield Hall, the home of Jane Eyre’s brooding Mr. Rochester.

During their lavish honeymoon, Judith and Gavin “memorized French poetry and they went to the most medieval places and indulged in the darkest and most outré thoughts”—while, that is, they weren’t engaged in oddly businesslike coitus (the unconvincing assertion that “she orgasmed over and over again” appears more than once). When they move into the dilapidated but picturesque castle, Judith is enraptured by her new life and setting: “She spent hours traipsing through the crumbling old halls, constantly finding new decrepit rooms with rotting wallpaper and broken-down furniture, musty secret passageways, and superfluous stairways that led nowhere, and she never tired of these adventures.” Yet the declaration of pleasure does not readerly pleasure make. Though Biller’s narrator makes sure to tell us how overpowering the erotic compulsion that ties Judith to Gavin is, and how self-destructive feeling like the heroine of a romance can be, the prose can read more like superficial parody than evocative pastiche. We understand Judith’s torment—but we do not feel it.

Part of the problem is that what chills and thrills in the eighteenth-century novel may not work for a twenty-first-century one. While exploring Manderfield’s moldering attic, Judith is terrified by a comically conventional tableau:

The room was cold and black as pitch. Her fingers scrabbled for a light switch, but when she flipped it, nothing happened. Then she heard a screeching sound, and something came flying straight at her head. She screamed and ducked, and a horrid furry bat, its fangs dripping, went flapping past her and down the spiral staircase.

Living, as we do, in post–Scooby-Doo times, it’s hard to read these words and not summon up cartoonish visions that detract from any real sense of dread. To take another example, the pathetic fallacy, a mainstay of gothic literature, also turns up in Biller’s novel. As Judith is torn between staying and going, the weather is obligingly dreadful: “The wind began moaning like a sad ghost, and the windows rattled like lugubrious chains, and the rain pattered down like knives stabbing her heart.” It’s hard to know how to respond to moments like this. While a satire of the form like Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey reminds readers of exactly what they might enjoy in the gothic novel while highlighting its pitfalls, Biller’s exhausted genre cues do the opposite, playing up their ridiculousness and distracting from the pathos of Judith’s worsening situation.

All this could be justified as part of Biller’s knowingly self-referential style. As she herself has noted, “the very first Gothic novel, Castle of Otranto, was already a pastiche of medieval romances, very tongue-in-cheek.” But even if the silliness is excused as intentional, what is the intention? One can’t be sure where the lines between irony and earnestness, ridicule and appreciation fall in this novel. Like Manderfield itself, whose artful ruination is both appealing and suspect to Judith, “The whole thing seemed more theatrical than practical, like a mausoleum for antique furniture and gilded objects—as if the décor was itself a folly, a façade, a bit of fakery to evoke grand and melancholy feelings.”

Biller is a well-read and canny interpreter of the gothic; the novel is peppered with references to intertexts, both overt and oblique (like the clear but unannounced allusion to Michael Powell’s 1963 telefilm of Bartók’s powerful and disturbing opera, Herzog Blaubarts Burg). Bluebeard’s Castle courts readers who, like Biller, are avid readers of both the sprawling family of Bluebeard retellings and gothic fiction with Easter eggs like this, eager to appreciate the research that went into this novel. But regardless of what readers bring to their encounter with the book, Biller’s preoccupation with formal and conceptual projects makes it difficult to connect with Judith’s story. The novel was originally written as a screenplay, and I imagine that if Biller had had the opportunity to realize it on film, viewers would more easily succumb to the atmosphere of sadness and terror the book tells us to believe is there (cue the moaning wind and shrieking rain). While Bluebeard’s Castle is busy summoning up the paraphernalia of genre or offering moralizing exposition, we miss what makes its numerous intertexts so seductive to readers like Judith: an undercurrent of frighteningly inexplicable eroticism.

Sarah Chihaya is the author of Bibliophobia, forthcoming from Random House.