Of the emotional afflictions we witness in those around us, obsession may be the most discomfiting. It’s also the most gendered: We’re conditioned to find it appealing, flattering when a man is the obsessed—Calvin Klein’s women’s fragrance “Obsession,” is, I assume, designed to elicit obsession from males who pass within smelling range of the female wearer, after all. But an obsessed woman? It’s likely people find her pathetic. In the case of Adam Foulds’s recent novel Dream Sequence, we see obsession engulf Kristin, a lonely divorcée who spends her time holed up in her TV room watching The Grange.

- review • October 17, 2019

- review • October 15, 2019

Early in Middlemarch, George Eliot’s young heroine finds herself alone on her honeymoon, bewildered by her disappointment in her new marriage. After describing Dorothea’s desolation, the narrator addresses the reader directly:

- review • October 8, 2019

History, Tolstoy insisted, is not driven by great men—the Bismarcks, the Napoleons of this world. It is constructed from an endless number of minute details, like drops of water, or grains of sand.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

The erstwhile wunderkind has been coping with the onset of middle age for four books now. The novels NW (2012) and Swing Time (2016) were about the ways youth slips away, among other things: friendship, neighborhood loyalties, class, celebrity, violence, inequality, biracial identity, sex, the internet, Africa, England, and how to write a novel when realism is anxious about its own survival. The essays in Feel Free (2018) and now the stories in Grand Union have taken in parenthood, the passing of the older generation, unexpected political upheavals, unwelcome physical transformations, and the arrival of a strange species: people in

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

At the midpoint of D. H. Lawrence’s Women in Love occurs one of the really extraordinary hidden scenes in English literature. Ursula and Gudrun are the young protagonists, figuring out their ambitions, their loves, and their futures. They are walking to a neighborhood water-party, with their father and mother in front of them, when suddenly they burst out in mockery. “‘Look at the young couple in front,’ said Gudrun calmly. . . . The two girls stood in the road and laughed till the tears ran down their faces, as they caught sight again of the shy, unworldly couple of

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

We all know that men don’t understand women. How could they? Women spend the whole time trying to understand themselves. “I specialize in women,” the writer Nancy Hale said in 1942. “Women puzzle me.” Hale felt that she knew how, “in a given situation, a man [was] apt to react.” (She’d been married three times by the age of thirty-four.) Women, on the other hand, vexed and intrigued her. Her mother, the portraitist Lilian Westcott Hale, made a career of looking at other women, including her daughter. In The Life in the Studio (1969), a memoir about growing up with

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

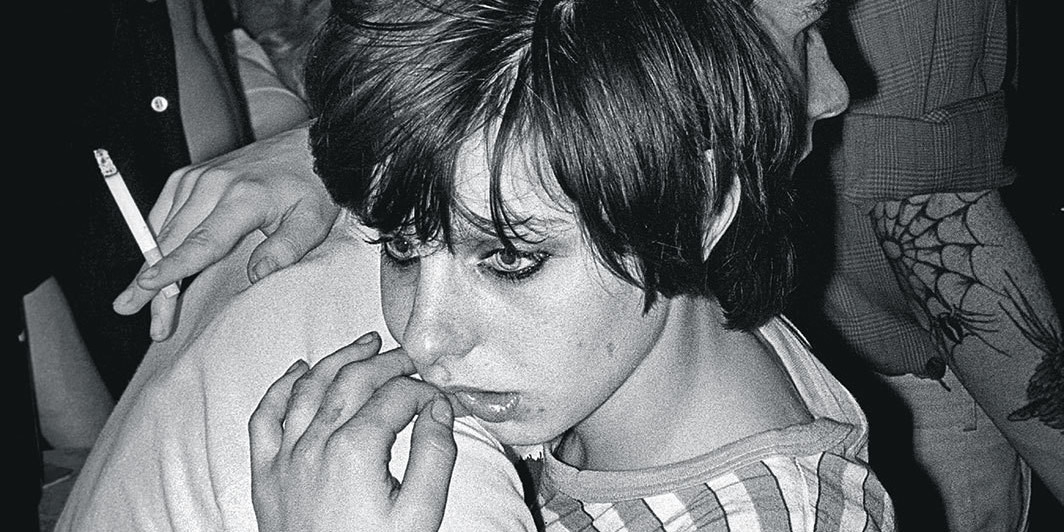

On October 17, 1973, Ingeborg Bachmann—the Austrian poet, novelist, librettist, and essayist—succumbed to burns sustained three weeks prior when she, tranquilizers swallowed and cigarette in hand, lay down to sleep and inadvertently lit her nightgown and bed on fire. She was forty-seven and had, since receiving the Gruppe 47 prize even before the 1953 publication of her first poetry collection, Borrowed Time, astonished the German-speaking public as well as esteemed peers with texts that pushed against tradition and played at the limits of language. She awed the likes of Günter Grass, Peter Handke, Uwe Johnson, Fleur Jaeggy, Elfriede Jelinek, and

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

In the eight years since a small group of anti-capitalist activists set up camp in Zuccotti Park, Occupy Wall Street has generated its own literary subgenre: Jonathan Lethem’s Dissident Gardens, Ben Lerner’s 10:04, Eugene Lim’s Dear Cyborgs, and Ling Ma’s Severance all feature scenes of the 2011 protests. In these novels, the Occupy movement, with its non-programmatic political aims and nonviolent tactics, represents a particularly utopian way of thinking about contemporary revolution—one that is less about direct action than it is about nonaction, about indirection.

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2019

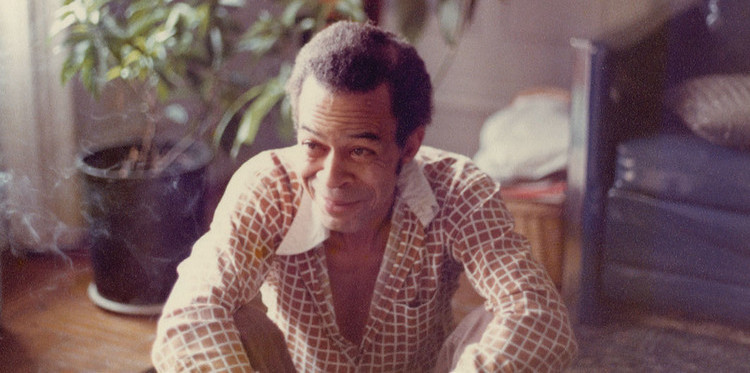

The decades of near-silence that came in the wake of Charles Wright’s trilogy of short novels seem almost as aberrant and disquieting as the novels themselves. Wright died of heart failure at age seventy-six in October 2008, one month before Barack Obama’s election and thirty-five years after the publication of Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About, the last of Wright’s novels, whose 1973 appearance came a decade after his debut, The Messenger. Wright clawed and strained from the margins of American existence for widespread acknowledgment, if not the fame his talent deserved. Cult-hood was the best he got, but it’s

- excerpt • August 22, 2019

“Little Women was about the best book I ever read.” So began my fourth-grade book report, in 1981. Clear, if uninspired. After one-and-a-half double-spaced pages of cursive rhapsodizing in support of this daring claim, I concluded with the lazy feint of an already overburdened critic: “I would like to go on and on with this report but it would be longer than the book, so if you want to find the rest out my opinion is to read it.”

- review • August 13, 2019

The year is 1927. A schoolteacher who twenty-three years ago showed up with a bicycle and a duffel bag in Thyregod, Denmark, has just lost her husband. Vigand was a cold, pretentious doctor. Once, he could barely be bothered to make a house call on a man who had swallowed his dentures. Vigand knew he was dying. He drove himself to the hospital. He checked himself in, wearing his new gray suit. He told none of this to his wife, twenty years younger and ten times warmer.

- review • August 7, 2019

Today’s challenges of transparency and opacity in everything from the personal to the institutional have created a desire to experience these qualities afresh in literature. I have often thought of these issues as lake-like, because lakes are eerily both. It is a psychic challenge to imagine what cold, still pools of water withhold below a calm, shimmering surface. The work of the Swiss writer Fleur Jaeggy is similarly lacustrine, typified by cool observations that quickly plunge into uncertain depths. Sweet Days of Discipline, set in the 1950s at an elite girls’ boarding school in Switzerland near the Alpine waters of

- review • July 24, 2019

The question that arises whenever a novel is reissued is “why now?” In the case of Suzette Haden Elgin’s Native Tongue, republished by the Feminist Press this month, the answer is evident: First published in 1984—one year before Margaret Atwood’s similarly dystopic The Handmaid’s Tale—Native Tongue is, depressingly, still extremely relevant.

- review • June 26, 2019

There is an oft-quoted line from the Talmud: “And whoever saves a life from Israel, the Scripture considers it as if he has saved an entire world.” Nathan Englander’s latest novel, Kaddish.com, is centered on a son’s preoccupation with saving his father’s soul—not for this world, but for Olam HaBa, or the World to Come. The novel is the Pulitzer Prize finalist’s most humorous and moving work since his best-selling debut collection, For the Relief of Unbearable Urges. Divided into four parts, Kaddish.com follows its protagonist’s transition, from secular, single, cynical Larry to devoted husband, father, and Yeshiva teacher Reb

- review • June 24, 2019

We live in “the Bad Timeline.” It’s a trope you see surface occasionally on social media, especially after some cartoonishly awful thing happens. The idea is this: At some point before Trump was elected or before 9/11 or before Vietnam (pick your generational trauma), reality cleaved in two. In one reality, the Bad Thing was averted. In ours, the Bad Thing happened.

- excerpt • June 17, 2019

A man named Osvaldo Ventura entered a boarding house in Piazza Annibaliano. He was square, stocky, and wore a mackintosh. His hair was grey-blond, his skin flushed pink, his eyes yellow. He tended to smile when he felt uncertain.

- review • June 12, 2019

Ali Smith is writing the world as it happens. In the vein of Charles Dickens, she has set out to reshape the serial form in her Seasonal Quartet of interwoven yet stand-alone novels, responding to the times, not in a mode of reflection but immersion, publishing as she goes. And what times to choose: best of, worst of, as it goes. To say that these have been eventful years, particularly in Britain still in the tenebrous haze of Brexit’s implosion, is beyond understatement. And yet Autumn (2017) and Winter (2018) both circle these political ups, downs, and side to sides

- print • Apr/May 2019

The Clinton Hill brownstone where Kathleen Alcott’s second novel, Infinite Home (2015), is largely set is about as far away from the Apollo program’s Lunar Module—Lem, in NASA-speak—as fictional territory can be. Edith, the elderly landlord of this neglected five-unit dream factory, hasn’t raised the rent in fourteen years and lives in closer communion with the neighborhood’s past than its multi-racial, gentrifying present; the tenants are eccentrics with maladies and psychic wounds that make it impossible for them to traffic in the world outside. One night, when Edith wanders disoriented into the stairwell, they all gather around to try and

- print • Apr/May 2019

Fifty pages into this novel—Susan Choi’s fifth—I was ready to write about it. I understood its design and I admired its execution. So let’s just start there—with what I knew. Two fifteen-year-olds, Sarah and David, attend a prestigious arts school, the Citywide Academy for the Performing Arts (CAPA). Neither can drive, but both can have sex. They fall in love, though this is probably not the right word for what they experience. Their love is colossal. Monstrous. Steamy and feral. They are kids entrained by desire into appearing older and more savvy than they are.

- print • Apr/May 2019

The protagonist of the linked short stories in Bryan Washington’s debut collection, Lot, does not give us his name—at least, not until we have earned this privilege. First, we have to let him usher us through Houston’s working-class neighborhoods and into the lives of queer people of color clinging to their jobs and homes as the city changes around them. The stories unfold in the confines of restaurant kitchens and cramped homes, places where the hard logic of economic precariousness can turn people into enemies just as easily as it can turn them into kin. In Washington’s portrait of the