The most striking scene in Who Killed My Father is also its most emblematic. The French novelist Édouard Louis revisits the memory six times in his brief new memoir-cum-polemic, sifting it obsessively as if for hidden information that the scene won’t yield. One evening in 2001, a preadolescent Édouard stages a performance for his parents and a large group of dinner guests. It’s standard proto-queer kid stuff: a now-dated pop song, fussy choreography, backup dancers conscripted from among the guests’ children, and the ringleader self-cast as front woman. The adults watch politely—all except Édouard’s father, who turns away. His withdrawal

- print • Apr/May 2019

- print • Feb/Mar 2019

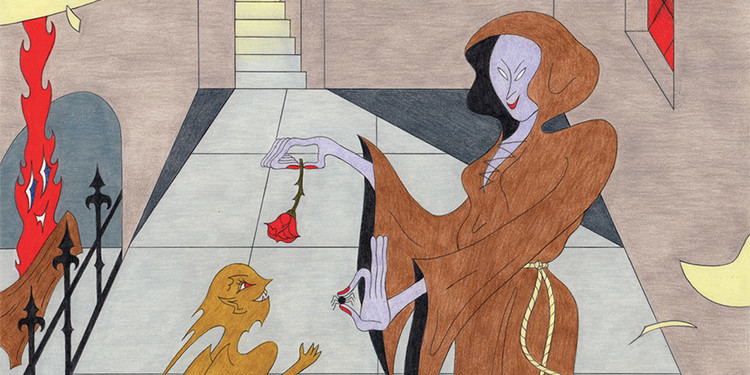

Terrible things happen in Kristen Roupenian’s You Know You Want This, a fact hinted at by the table of contents, which reads like a list of YA vampire novels: “Bad Boy,” “Death Wish,” “Scarred,” “Biter.” “I write horror stories,” the author told the Sunday Times last year. “The pull and push of revulsion and attraction is what the book revolves around.”

- print • Dec/Jan 2019

How good was Lucia Berlin? She published her first story in 1960 at age twenty-four, but her debut volume, Angels Laundromat (1981), wouldn’t appear for another two decades; Phantom Pain followed in 1984, and Safe & Sound in 1988; all three came out with small presses. Her readership grew slightly when Black Sparrow Press took her up, publishing Homesick (1990), So Long (1993), and Where I Live Now (1999), but even their support wasn’t enough; nor was the esteem in which Berlin’s terse and minimal style was held by Lydia Davis, Saul Bellow, and Raymond Carver. By the time A

- print • Dec/Jan 2019

Virginie Despentes and Coralie Trinh Thi, Baise-moi (Rape Me), 2000. Manu (Raffaëla Anderson). ON THE NIGHT the French author Virgine Despentes was gang-raped, at age seventeen, she had a switchblade in her pocket but was too terrified to use it. “I am furious with a society that has educated me without ever teaching me to […]

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2018

NO WORKING WRITER believes in the shattering power of an encounter—with another person, with a new sensation, with possibility—more than Amélie Nothomb, the prolific Paris-based Belgian who’s published a novel a year since 1992’s Hygiène de l’assassin (rendered in English as Hygiene and the Assassin, though a more accurate title would be The Assassin’s Purity). Her first book offered an impressive blueprint of what would define her subsequent work: arrogant, infuriating personalities; vicious character clashes; childhood love so obsessive that it bleeds out over an adult’s entire history; and philosophical declarations about war. (Nothomb’s fervent worship of “war,” used to

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2018

In his visionary 1985 essay “Exactitude,” the Italian writer Italo Calvino says, “The literary work is one of these tiny portions in which the existent crystallizes into a shape, acquires a meaning—not fixed, not definitive, not hardened into mineral immobility, but alive, like an organism.” This declaration is just one of the many and various ways that he tries to articulate the relationship between form (finite, distinct, structural, shapely like a crystal) and the infinite (everything in the natural universe that exists and can be imagined), a tension so essential that it could be said to describe all writing, all

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2018

IT IS ONE THING to write down the shameful truth of what you really think about someone else; another to publish that shameful truth inside a novel. It is, perhaps, a third thing to use, within your novel’s pages, that person’s actual name, and a fourth to render it all in prose whose rawness will flatter no one. It is something else, however, if that person is your wife.

- print • Summer 2018

Entirely pristine in its styling, Ottessa Moshfegh’s fourth book, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, opens with the phrase “Whenever I woke up . . .” It is understated, implicit wording—the mild “whenever” simultaneously pointing to no precise time and to various specific times. The words “I woke up” crackle with multiple meanings. Woke from a slumber; woke from a stupor; woke from ignorance; woke from delusion; emerged from grief; emerged revived. It all applies. For a book about a woman so broken and exhausted by life at twenty-four that she sets out to sleep for a year, there couldn’t

- print • Summer 2018

FAYE HAS JUST BOARDED an airplane when Kudos, the third novel in a trilogy about her middle life, begins. She boarded, after lunch with a billionaire, another airplane at the start of the first novel, Outline. She was reading a spam e-mail from an astrology service predicting “a major transit . . . in [her] sky” when the second, Transit, began. Passenger flight explains these incredible novels. At first, for several pages, it’s hard to relax. Why must we be in this stifled, banal environment, with no room to think? How long do we have to sit here? The air

- print • Apr/May 2018

When Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation came out in 2014, I couldn’t elbow my way to the bar without having a conversation with a woman writer about whether or not we knew any art monsters. Ottessa Moshfegh? Even Kate Zambreno and Joy Williams have children. . . . It seemed fitting we were all suddenly preoccupied with this question, as if we’d found a way to talk about whether or not we wanted to be geniuses, like the men.

- print • Feb/Mar 2018

IN TATYANA TOLSTAYA’S EARLIER SHORT-STORY COLLECTION, White Walls, a character remarks, “If a person is dead, that’s for a long time; if he’s stupid, that’s forever.”

- print • Apr/May 2018

A fan of Alan Hollinghurst’s masterpiece The Line of Beauty has created a Twitter account, @lollinghurst, to document the many epigrams and sly jokes and thrillingly acute descriptions found throughout that novel. These “lines of beauty” don’t just serve to decorate the book; they are the book. “His lips quivered and pinched with the sarcastic alertness that was his own brand of happiness.” “He felt victimized, and flattered, pretty important and utterly insignificant, since they clearly had no idea who he was.” In The Line of Beauty, Hollinghurst evokes inner states and interior decor with effortless mastery; both of them

- print • Feb/Mar 2018

I don’t know whether or not The Friend is a good novel or even, strictly speaking, if it’s a novel at all—so odd is its construction—but after I’d turned the last page of the book I found myself sorry to be leaving the company of a feeling intelligence that had delighted me and even, on occasion, given joy.

- print • Dec/Jan 2018

I’ve heard it argued—and I agree—that fiction that builds a universe whose rules depart from our own allows for the contemplation of ethical dilemmas that cannot be addressed in or by the world as we know it. This kind of fiction—what my toddler might call “same but different”—tends to disrupt our go-to feelings. In an alternate universe, you are moved to relitigate the basics because you cannot take anything for granted. The sun is black; the moon is pink; everything we know needs to be reevaluated—the facts of our lives and, by extension, the principles we hold dear. Similarly, fiction

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

In a 1966 essay for the New York Review of Books on divorce in America, the sociologist Christopher Lasch remarked: “Divorce is a depressing subject from almost any point of view. For participants, it is not likely to be an ennobling experience; nor does it have the compensatory virtue, like other forms of suffering, of lending itself to literary uses.” Because divorce tended to throw dignity out the window, it was beneath the tragic mode, and the subject simply put off writers with comic talents. “Grim earnestness” or “sensationalism” seemed to be the two modes available to writers treating the

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

Faulkner had Yoknapatawpha County and Jesmyn Ward has Bois Sauvage—neither real, both true. Faulkner reimagined Lafayette County, in the northern half of Mississippi, while Ward has used Bois Sauvage in three novels to stand in for the small towns of the Mississippi Gulf Coast, which could include DeLisle, where Ward grew up. Ward’s 2008 debut, Where the Line Bleeds, is about twin brothers struggling to get by in Bois Sauvage. Salvage the Bones (2011) follows Esch, a pregnant teenager who loves Greek mythology, living in the days before Hurricane Katrina. (This won Ward the National Book Award for fiction.) Sing,

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2017

I know it’s not a popular opinion, but I’ve always felt that Saul Bellow did some of his finest work in the short story. They’re almost all novella-length, but even so, the limit imposed by the form provides a propitious counterforce to Bellow’s natural maximalism, and the results feel simultaneously epic and economical. I readily rank his Collected Stories up there with Herzog and Augie March at the apex of the Bellow canon—assuming, which I suppose I shouldn’t, that such a thing still exists. Moreover, Bellow’s stories often find him mining his early, formative experiences as the child of Lithuanian

- print • June/July/Aug 2017

On the morning of June 9, 2012, Avtar Singh called 911 in Selma, California, to say that he had killed his family and was about to turn the gun on himself. When the police reached his house, they sent in a robot equipped with a camera. The feed from the robot showed Singh lying dead in the living room. His wife and two sons were also dead; a third son, the eldest, was still breathing, but he died from his wounds five days later. Each person had been shot in the head.

- print • June/July/Aug 2017

The index card pinned to an unassuming bulletin board is catnip for lonely women with bad day jobs—the types who spend late nights at AA meetings in church basements and do their own wash-and-fold in sticky, twenty-four-hour laundromats. Listless and desperate for change, bored in depressing, utilitarian cityspaces, they try contacting a stranger.

- print • Apr/May 2017

When you sit down to read a review, as you are doing right now (unless you are standing—in which case, please sit down and take a minute), you rarely have a sense of where the critic is writing from: what time of day it is, what she has eaten, what else she has just read or seen, what’s on her mind. But all of this factors into the work, just as wherever you are as a reader, and how you are feeling, will, too. The pleasure of a critical essay can often be the escape it grants from diachronic time;