THE GREAT AMERICAN NOVEL was for most of the previous century a golden icon, an aspirational myth of grand and glittering proportions. Though he never attained that grail, Seymour Krim, an ardent worshipper at its altar, perhaps best articulated the dream in a 1968 essay in which he described the hopes of fellow aspirants to “use the total freedom of our imaginations to rearrange the shipwrecked facts of our American experience into their ultimate spiritual payoff.”

- print • Winter 2024

- print • Fall 2023

HOW ROMANTIC IS J. M. COETZEE? At first the question, prompted by his eighteenth novel, The Pole, sounds like a joke. The journalist Rian Malan, who visited Coetzee’s office at the University of Cape Town in the early 1990s, reported that the novelist didn’t smoke, drink, eat meat, or, except on very rare occasions, laugh. “It helps to have a piercing gaze,” Coetzee wrote in one of eight essays on Beckett, and his own author photographs show a man who, with his ironed shirts, unvainly swept-back hair, and eyes that would win any no-blinking competition, resembles a semi-retired notary public, or

- print • Fall 2023

IF THE TITLE of Helen Garner’s 1984 novel, The Children’s Bach, could strike a chord, it would be a diminished seventh—an unexpected tone of dissonance, curling toward the uncanny, eager for resolution. The title is borrowed, as chords often are, from a 1933 collection of Bach’s easier pieces, edited by E. Harold Davies and still in print. The instructional text telescopes into the novel: Garner’s character Athena is learning to play piano, pinched by determination in the absence of natural talent, no longer the hypothetical child of Davies’s intent. She is the mother of two sons, home for long afternoons as

- print • Fall 2023

IN JUSTIN TORRES’S NEW NOVEL, Blackouts, disorientation is a pleasure. You might wonder, at first, if you’re being duped by these characters or invited to share in their confusion. We’ll get to the reasons for that confusion, which is to say the plot, but plot is less the point than form and a nebulous atmosphere. Short chapters, shifting perspectives, and doctored photographs give the novel the air of an enigma to solve.

- print • Fall 2023

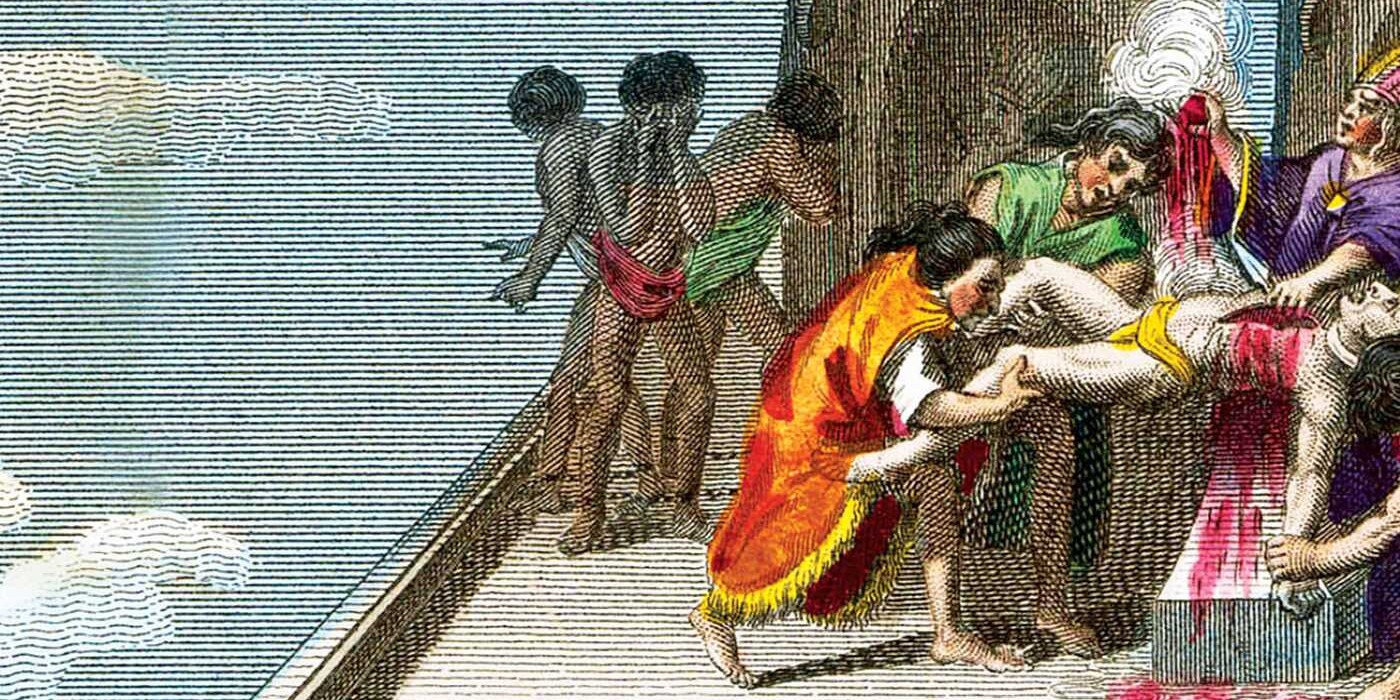

WHEN ELIZABETH BENNET AND HER SISTERS sit in calico dresses awaiting the favor of a man of “10,000 a year,” the link between that income and that calico remains easily ignored. So easily, that fantasies of Regency romances endure to this day unburdened by discomfiting questions about the origins of the cotton in these drawing-room dramas. By comparison, any respectable circle in the US would know better than to insist, in this decade at least, upon the charm and romance of the antebellum South. One could not produce a Bridgerton set in Alabama as easily as Netflix produced one set in

- print • Fall 2023

NOT TO MAKE THIS review about me or anything, but about ten years ago I published a big book with multiple characters and story lines. My dad, then in his seventies, said I should have included a character list and roadmap because he had trouble following it all. I remember thinking, in response, that he’d obviously gotten old and slow and that his tastes were conservative and fuddy duddy. Today, I’m willing to concede I might have turned into this same fuddy-duddy, which I offer up as context for my thoughts on Ed Park’s—what is the right adjective here? discursive? fascinating?

- print • Fall 2023

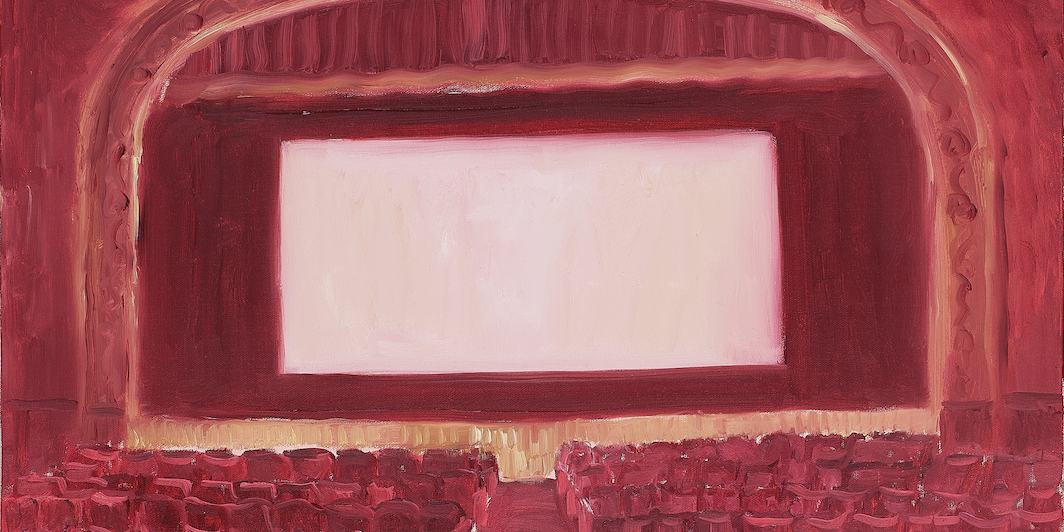

I HAVE FREQUENTLY BEEN SEATED in the dark near those who have variously been called “the pilly-sweater crowd,” “cinemaniacs,” or “Titus-heads” (referring to the two main movie theaters at MoMA). They are pejorative terms for a certain type of New York City cinephile, one whose zeal for the seventh art seems to have been leached of all pleasure and has instead transmogrified into grim compulsion. Demographically, they are often (but not always) white, male, and middle-aged or older.

- print • Fall 2023

NOVELISTS ARE LUCKY. Not only is their “I” a fiction—even or especially when the veil is of the gossamer kind—but when they need some space to say what can only be said when “I” is another they can always switch to third person. The critic tends to get stuck in first. So I find myself in a waiting room, just as he does. I am in New York and he—Tunde, a photographer, writer, professor and sometimes narrator in Teju Cole’s novel Tremor—is in Boston. His friend and colleague Emily has cancer. The tests or treatments she is undergoing might give

- print • Fall 2023

WHEN A NOVELIST’S sophomore novel is narrated by a novelist bemoaning the New York Times review of her first novel, even the most auto-skeptical critic might be forgiven for pulling up a search window. Turns out that the Times review of Lexi Freiman’s Inappropriation (2018) is nothing like the “cancellation” her character, Anna, undergoes in The Book of Ayn. However, the review does begin by declaring that “Satire is a difficult genre to neatly define,” followed immediately by a definition that is roughly what you’d get by googling “satire definition.” You can hardly blame Freiman if reading these words in

- print • Fall 2023

THERE’S A PHOTOGRAPH of the writer Sigrid Nunez as a young woman, sometime in her mid-twenties. It is 1977 and she has graduated with an MFA from Barnard, having studied under Elizabeth Hardwick. In the picture, Nunez is quite literally radiant—her gleaming teal top echoes the light bouncing off her high cheekbones.

- print • Summer 2023

REMEMBER WHEN THE worst thing was death? AIDS, cancer, COVID—a horror for the people who died (are still dying) and a massive source of anxiety for the rest of us. And yet as my daughter and I waited out lockdown—fwiw, my daughter in this context represents the zeitgeist—she never once worried about us dying from COVID. Nope, she’d already assimilated death anxiety into her shelf of bedtime reading, the old standards. Instead, her fear had stepped up and out on a ledge overlooking apocalypse. Climate change. The end of everything. Extinction.

- print • Summer 2023

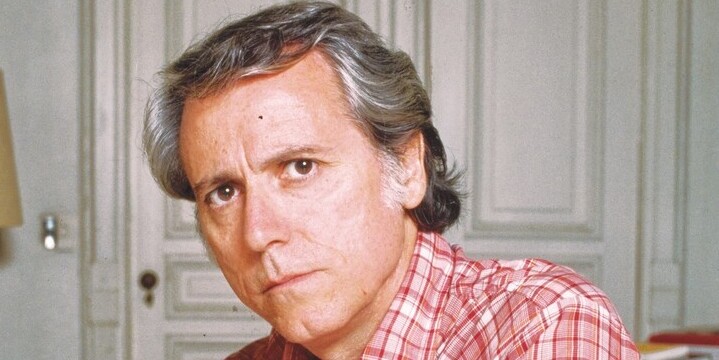

THE CRITIC Ian Penman’s Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors is a work of biographical criticism with strong views on the genre’s pitfalls and limitations. Right at the outset, he pronounces “the absolute impossibility of summing up” his subject, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and promises that this auteur monograph will not stoop to “plot outline and capsule description.” He questions the very point of “biography or overview or memorial or accounting in this era of Wikipedia and Twitter and all the other just-a-click-away info blocs and image banks.” And he bemoans the “dulling effect of canonization,” citing as a negative model Sartre’s biography

- print • Summer 2023

THE DREAM OF AN ARTWORK that encompasses the whole world; of a novel that tells everybody’s story; of characters who feel and act and speak for us all; of the image that nobody doesn’t recognize. Yet it is the world and characters and images and stories themselves that stand in the way of that dream. They are too real and too small, too specific and too discrete to be for all. A person personifying history is still a person, history warped by and warping a personality. A dramatic narrative consists of speeches, acts, events. A consciousness is marred by the

- print • Summer 2023

I WAS SEVENTEEN AND IN MY THIRD YEAR OF FRENCH when I learned the phrase la petite mort: “the little death.” The boy in class I had a crush on—what was it he called himself? Roland, Jean-Pierre, Henri?—informed me, whispering so Madame Chrétien wouldn’t overhear us, that it was meant to describe an orgasm, or rather (I discovered later, after experiencing more than the panicked fumbling of high school trysts), the untenanted feeling that comes after having had one. Of course, I thought, of course, great sex would be something like an annihilation of the self. In my diary, I

- print • Summer 2023

IN HANGMAN, MAYA BINYAM’S engrossing and shrewd debut novel, the author cultivates a world in which many languages are spoken but few are understood. After twenty-six years, an unnamed narrator finds himself on a flight traveling from what seems to be the United States back to his African homeland. He has just listened to the man sitting next to him tell a story about his life when a flight attendant asks if he would prefer tea or coffee. Though it is a routine question, she must switch languages for him to realize that he has a preference: coffee. With that

- print • Summer 2023

THE DUBLIN-BORN NOVELIST PAUL MURRAY, who entered adulthood during Ireland’s rapid modernization in the 1990s, writes fiction about the problems that modernity everywhere has failed to solve. His characters come up against cruelty and abuse, inequality, grief, terrible loneliness, death—but generally their problems boil down to one of two sources, their families or their money. Murray’s 2010 boarding school–set bestseller, Skippy Dies—with its fucked-up children of sick or divorcing parents, its neatly bidirectional line between the traumas of childhood and the disappointments of adulthood—tilts toward the former, resulting in a warmly humane novel with an occasional YA-ish texture. In 2015,

- print • Summer 2023

LORRIE MOORE’S NEW NOVEL STARTS TWICE. The first chapter is a letter from one sister to another, an old one, probably, because who writes letters anymore and I don’t even know what a “desk cartonnier” is but it sounds old. I can’t quite place the year or state but the period and region are clear: the Reconstruction South. “I have also sent Harry some old rebel coins for pounding into cufflinks,” our narrator, an innkeeper named Elizabeth, writes, as if to say, There will be no Confederate relics in my lodge. Canadian coins, oddly enough, circulate, but one senses that

- print • Summer 2023

ONE STURDY WAY TO UNDERSTAND WRITER and director Henry Bean is as a specialist in the study of extremely bad behavior. His best subjects are the worst: self-hating havoc-wreakers, or the “I Suffered Complicated Trauma and Now the World Has to Deal With It” type. Populating his catalogue of asshole picaresques—rich with vicious couplings, drunken confrontations, alfresco autoeroticism—are a secretly Jewish neo-Nazi played by a skinhead Ryan Gosling (The Believer, 2001), a sledgehammer-and-baseball-bat-wielding vandal (Noise, 2007), a sexy serial murderess (Basic Instinct 2, 2006), and the protagonist of his only novel, a writer who presents his latest project as a

- print • Summer 2023

WHEN WE FIRST MEET HER, Alex is adrift—literally at sea, floating perilously farther away from shore. “What would they see if they looked at Alex?” she wonders, gazing on the rest of the beachgoers. “In the water, she was just like everyone else.”

- print • Summer 2023

IT WAS THE FALL of the Berlin Wall that prompted Jenny Erpenbeck to become a writer, as if the beliefs and structures guiding her life that had, almost overnight, been rendered obsolete, could be recuperated by language. But Erpenbeck, born steps from the Wall in 1967, wasn’t interested in memoir or commemoration. She preferred tricks of self-effacement, recursion, deferral, anything that lent “freedom from the compulsion of realism.” Her debut, The Old Child (1999), is a parable of a loser’s triumph: a young woman posing as a fourteen-year-old goes to live in a children’s home, turning life into a game