SOMETIMES WHAT CONSERVATIVES SEEM TO FEAR MOST from liberals is not their money or their ideology but their judgment. Beneath the vast tide of right-wing grievance, there is a current of profound insecurity, a suspicion that liberals don’t think conservatives are good enough. There is nothing they desire more than the sight of a liberal humbled into seeing the light. To cater to this desire, the media has produced a peculiar new kind of pundit: the conservative who pretends to be a liberal—one agreeing, in spite of themselves, with the conservatives.

- print • Spring 2024

- print • Winter 2024

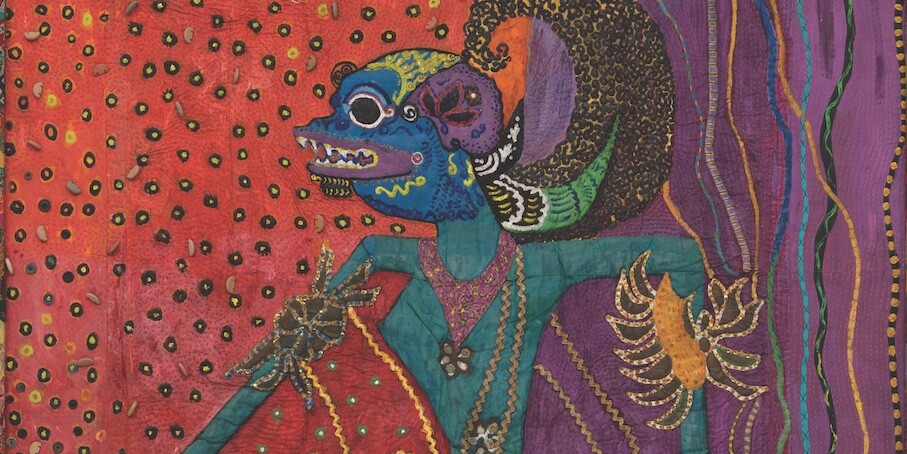

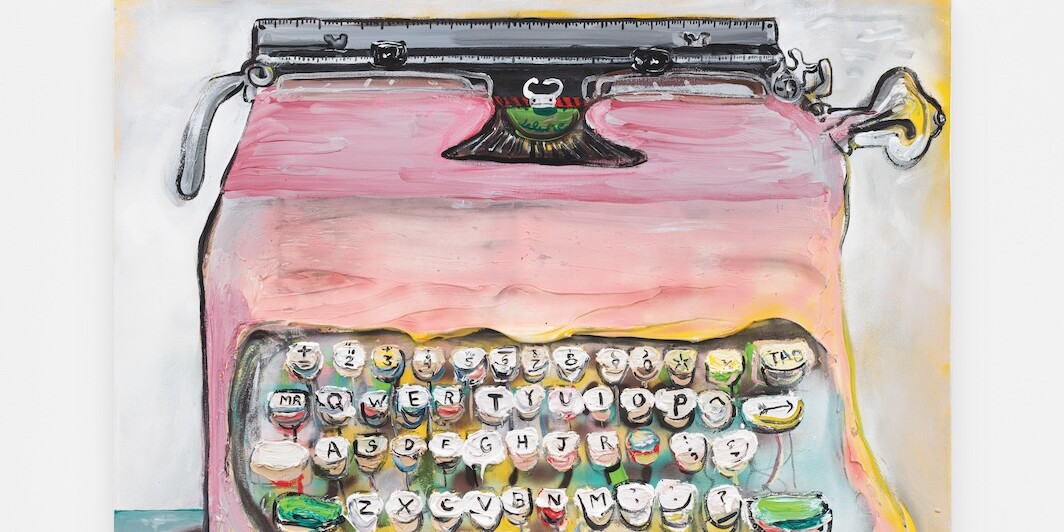

IT IS A FITTING IRONY that when trying to describe Anne Carson’s sensibility, one quickly hits the limits of language. To measure the breadth of her brain across her twenty or so books, one might acquiesce to hyphen-chic—as in, she is a poet-translator-scholar-of-ancient-Greek-essayist-visual-artist-playwright-maker-of-performances-and-dances—but such frantic stitching would fail to impart how seamlessly entwined her practices are. To distinguish her literary occupation from that of other authors, one might be tempted to conjure a new word via the dark arts of negation—she is an uncontainer of ideas, or she de-forms thought—but that would belittle her writing as merely an act of resistance

- print • Winter 2024

IN A 2014 INTERVIEW with Entropy Magazine, poet-filmmaker-scholar-anarcho-feminist-writer and dreamer Jackie Wang apologetically names a “piece of art that has recently undone/inspired you” as Lars von Trier’s Nymphomaniac. “What was it that made me receptive?” she wonders. “I don’t want to credit Lars von Trier!” Wang’s ALIEN DAUGHTERS WALK INTO THE SUN: AN ALMANAC OF EXTREME GIRLHOOD (Semiotext(e), $18) is perhaps not strictly an “art book,” but I make no apologies for selecting it, and I do want to credit Jackie Wang. Modestly illustrated with doodles, some black-and-white film stills, and stray photo nuggets, the book is no “sumptuous” display-case feat

- print • Winter 2024

THE FIRST THING I NOTICED about 1962’s Cléo from 5 to 7, one of the more enduring hits from filmmaker and artist Agnès Varda, is that the run time is not two hours but ninety minutes. Where did those thirty minutes go? How did she make a “real-time” film that doesn’t execute its promise? I always neglect to keep tabs on that missing half hour; I’m enjoying the film too much. Such is Varda’s slippery genius. She creates a structure, then leaves just enough room to show you how she did it—if you know how to see it. Varda knew all

- print • Winter 2024

AT THE BEGINNING OF DECEMBER, music-streaming behemoth Spotify laid off 1,500 employees. It was its third set of axings last year in response to the tightening of capital markets, altogether adding up to more than a quarter of its global staff. But this round was different, because it included Glenn McDonald.

- print • Winter 2024

MIDWAY THROUGH ABOUT ED, Robert Glück revives a line by Frank O’Hara: “Is the earth as full as life was full, of them?” Referring to three of O’Hara’s recently deceased friends, the line appears in “A Step Away from Them,” where it clangs against the rest of the poem and its meandering attention to noontime activity in midtown Manhattan, 1956. It perplexes Glück, whose About Ed remembers Ed Aulerich-Sugai, a lover and friend who died of AIDS-related complications in 1994. “The misdirection threw me,” Glück writes, “from the earth being full, to life being full, instead of Ed being full

- print • Winter 2024

IN THE POEM “POST,” from her posthumously published collection, The Cipher, Molly Brodak writes:

- print • Winter 2024

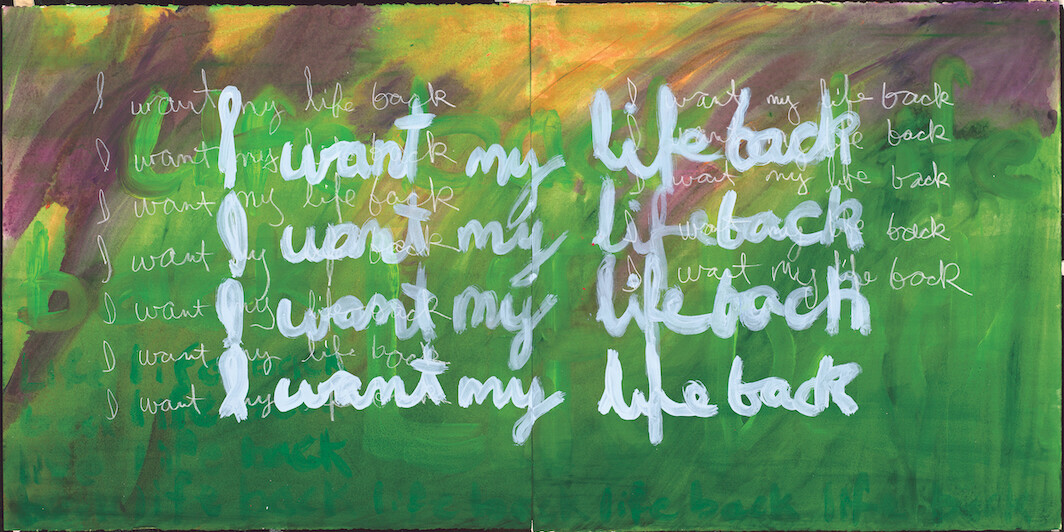

THIS IS ONLY AN OPINION, BUT: no one should make art about their divorce until they’ve experienced at least one heartbreak after the marriage’s end. I keep an inventory of all the times I encounter an artist who manages, in telling a story about a divorce, to also include the story of another breakup that followed the supposedly definitive one. I love to see anything that complicates more straightforward accounts of life after divorce. That next heartbreak—the more devastating, the better—must be reckoned with, because it dispels any remaining illusions, or maybe delusions, about what one is capable of in

- print • Winter 2024

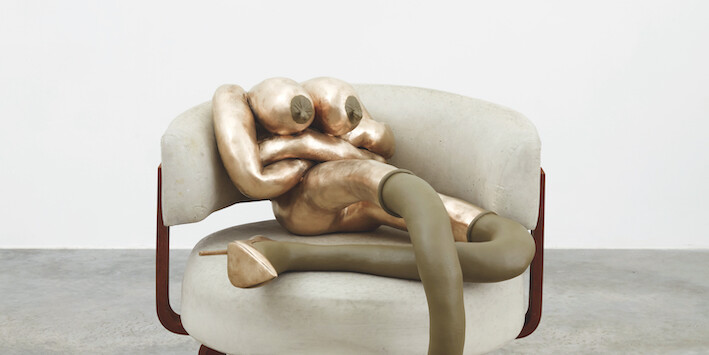

Sarah Lucas, CROSS DORIS, 2019, concrete, bronze, steel, iron, and acrylic paint, 28 1/8 × 28 3/4 × 26 3/4″. Image: Private collection. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London © Sarah Lucas. ARE WE ALLOWED TO ENJOY THIS? Chicks and dicks, fags and chicken thighs? Sarah Lucas’s sculptures use corner-store staples—bananas, cigarettes, a […]

- print • Winter 2024

IF, AS CLAUDE LÉVI-STRAUSS PROPOSED, “the purpose of myth is to provide a logical model capable of overcoming a contradiction,” then the act of keeping a diary, that practice of private self-mythology, is at least partially an attempt to overcome the contradictions inherent in a self. Granted, there’s a raft of differences between myths passed down over eons and those made about oneself within the span of a single life. The myth of Icarus, for instance, has survived due to its decisive ending and moral weight. But self-mythology—whether in the form of a journal, internet persona, or daydreaming—is a molten

- print • Winter 2024

WHAT IS AN AUTHOR? A conduit for the divine or a poor schlub combining and recombining stale units of meaning? Both answers share the assumption that a literary work is the product of one consciousness. This assumption is a kind of spell: even a book’s acknowledgments, where the many other hands that went into its making come into view, or its publisher’s colophon, which advertises the institutional infrastructure behind the text, cannot totally ward it off.

- print • Winter 2024

Mulligan’s pub, Joyce cat, from Evelyn Hofer: Dublin (Steidl, 2023). © 2022 Estate of Evelyn Hofer. “I’M NOT EVEN INTERESTED IN MOMENTS.” The German photographer Evelyn Hofer (1922–2009) knew her aesthetic was in some ways at odds with her time; her postwar streets and squares are emphatically not in the style of Henri Cartier-Bresson and […]

- print • Winter 2024

WILLA CATHER WAS A MASTER OF BEGINNINGS. O Pioneers! (1913), her first novel after the false start of Alexander’s Bridge (1912), opens on a provocatively odd note: “One January day, thirty years ago, the little town of Hanover, anchored on a windy Nebraska tableland, was trying not to be blown away.” Soon the attention shifts to the “cluster of low drab buildings huddled on the gray prairie, under a gray sky . . . set about haphazard on the tough prairie sod; some of them looked as if they had been moved in overnight, and others as if they were

- review • February 6, 2024

The Winter 2024 issue of Bookforum is online now! In this edition: Gene Seymour revisits John A. Williams’s unsung 1967 novel, The Man Who Cried I Am; Jennifer Krasinski writes about Anne Carson’s unruly art of renewal; Carl Wilson considers Kyle Chayka’s book on algorithms and our supposedly flat new world; Jamie Hood reads Blake Butler’s anguished portrait of his late wife, the poet Molly Brodak; Katie Kadue reviews My Weil, Lars Iyer’s reconfigured campus novel; Kay Gabriel explores loss, abundance, and time in Robert Glück’s About Ed; and so much more. Also: reading recommendations on the war in Gaza, a

- review • December 5, 2023

Welcome to the Fall 2023 issue of Bookforum! In this edition, our contributors review new novels by Ed Park, J. M. Coetzee, Zadie Smith, Teju Cole, Lexi Freiman, and more. Also in this edition: Katie Kadue reads scene stealer and meme factory Julia Fox’s memoir; Hanif Abdurraqib writes about obsession, mythology, and Will Hermes’s new biography of Lou Reed; Audrey Wollen considers Helen Garner’s newly reissued 1984 novel The Children’s Bach; Laura Kipnis reads Janet Malcolm’s posthumous confessional memoir; Jane Hu surveys Sigrid Nunez’s quietly defiant fiction; and so much more.

- print • Fall 2023

“WHO IS Julia Fox?” This is the question taken up by Fox’s highly anticipated memoir Down the Drain (Simon & Schuster, $29)—so highly anticipated, in fact, that I was required to sign an NDA promising I wouldn’t leak any details from the press copy I received, the plain white cover of which read only, enticingly, EMBARGOED. It was also the question some of my, frankly, uncool friends and acquaintances asked me when I excitedly told them I was reviewing Fox’s book. “Josh Safdie’s muse?” I prompted. “Actually, she’s her own muse. You know . . . Uncut Gems?” I pronounced it “unkah jamz,”

- print • Fall 2023

WE LIVE IN CONFESSIONAL TIMES and the self-exposure bug eventually comes for us all, the steeliest of non-disclosers, no less. We age and turn inward, we become garrulous and spill. Even I, who once fled the first-person singular like a bad smell, now talk about myself endlessly in print, opening every essay or review with some “revealing” anecdote or slightly abashed confession, striving for the perfect degree of manicured self-deprecation and helpless charm. Needless to say, the more forthcoming you appear, the more calculated the agenda, not always consciously.

- print • Fall 2023

Marne Lucas and Pippa Garner, Get Out, Get Under, 2015, digital print, dimensions variable. Courtesy: the artists AFTER BEING KICKED OUT of art school for creating a model car with human legs that looked like it was pissing on a map of Detroit, the Conceptual artist Pippa Garner built her infamous Backwards Car (1973–74), reconfiguring a […]

- print • Fall 2023

BEYOND AN OLDER SIBLING’S headphones wringing the sweet, distorted fuzz of the Velvet Underground out and into my ears, my second most notable encounter with Lou Reed was in the pages of the Lester Bangs anthology Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung, which has a whole section dedicated to Bangs and his relentless sparring with Reed. A book within a book, almost. There are two interviews that would, today, seem alarming in both their approach and the nature of their candidness, with Bangs demeaning Reed’s pal David Bowie, Reed taking the bait, Bangs shouting that Reed is full of shit. The

- print • Fall 2023

IN THE AWARDS-SWEEPING 2021 documentary Summer of Soul, a man named Darryl Lewis recalls his first Sly and the Family Stone encounter, at the Harlem Cultural Festival of 1969. In those days, he says, “When you saw a Black group, what you expected to see was, generally speaking, all men, all dressed in matching suits, ready even before they hit the stage to perform.” But here, Sly and company “kind of saunter out,” men and women, Black and white, a living quilt of psychedelic patterns, knit caps, and sundry frippery. “The instruments weren’t tuned,” Lewis says. “You wonder, What are they