In a letter toward the end of Love, Icebox, a collection of correspondence from John Cage to his partner Merce Cunningham, doubt about their relationship creeps in. Cage, who was seven years older than Cunningham, is concerned that Cunningham doesn’t love him and “will love other misters.”

- review • March 24, 2020

- review • March 17, 2020

Rob Doyle is a twentieth-century boy. His characters are monologous young men who get high and chase literary grouches with an eye out for that high-modernist whale, the epiphany. Many of Doyle’s contemporaries—literary men in their late thirties—confine themselves to the cramped emotional tone afforded to those invested in the internet’s panoramic view and its plausibly crushing Bad News. But Doyle looks back: His drugs and bands and writers are pre-9/11 specimens, across all of his books. The characters in his 2014 debut novel, Here Are the Young Men, are teen grads in Dublin off their faces, smack-dab in the

- excerpt • March 12, 2020

Part of a political revolution toward socialism will necessitate a revolution of values. Those values won’t come from the top down but from culture up. We can use Denning’s notion of a “cultural front”—in this case, to save us from our cultural ass. Right now the United States is working at a deficit. Our identities and aesthetics are deeply tied into capitalism—no disrespect to rapper Cardi B and her love of money, but unlearning money worship and our worth being determined by what we can accumulate is going to be vital to any socialist change. And as during the 1930s

- excerpt • February 20, 2020

My 1915 edition of The Cry for Justice by Upton Sinclair is an evocation of a lost America. The anthology is filled with writings, poems and speeches by radicals and socialists who were a potent political force on the eve of World War. They spoke in overtly moral and often religious language condemning capitalist exploitation as a sin, denouncing imperialism as evil and vowing to end the greed, cruelty and hedonism of the rich. The fight for justice for the poor and the worker was a sacred duty. The life of the artist was a life of action. Intellectuals, grounded

- excerpt • February 11, 2020

A weeping woman is a monster. So too is a fat woman, a horny woman, a woman shrieking with laughter. Women who are one or more of these things have heard, or perhaps simply intuited, that we are repugnantly excessive, that we have taken illicit liberties to feel or fuck or eat with abandon. After bellowing like a barn animal in orgasm, hoovering a plate of mashed potatoes, or spraying out spit in the heat of expostulation, we’ve flinched in self-scorn—ugh, that was so gross. I am so gross. On rare occasions, we might revel in our excess—belting out anthems

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

The title of Fleabag: The Scriptures (Ballantine Books, $28) is a cheeky play on words: It refers to the shooting scripts for the television comedy Fleabag, which are reproduced here in full, and it also refers to the fact that the second (and, if creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge is to be believed, final) season of the show, which debuted on Amazon Prime in May 2019, is about the main character’s romantic attachment to an unattainable Catholic priest. But it also acknowledges that Waller-Bridge’s words—printed out on creamy paper stock, bound inside a smooth navy-blue cover, and embossed with gold serif letters

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

Nam June Paik, Bye Bye Kipling, 1986, video, color, sound, 30 minutes 32 seconds. © Estate of Nam June Paik, Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York It’s misleading that Nam June Paik has been named the grandfather of video art. Sure, he started the whole thing, but as an artist, Paik is no patriarch. […]

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

“So Bert and Mary Poppins definitely used to fuck, right?” One Saturday night last winter some friends had gathered in my living room to reconsider one of our favorite childhood movies through the cracked lens of our millennial adulthood. (A very millennial thing to do: In our minds it was subversively ironic, but to the skeptical observer we just looked like a bunch of thirtysomethings so infantilized and brain-fried by pop culture and social media that we were spending the prime time of our weekend watching a Disney movie.)

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

Elizabeth Hardwick was a worrier. “What I know I have learned from books and worry,” she wrote in Vogue in June 1971. She worried about her daughter Harriet’s grades in school. She worried about rising rents in New York City and about the price of property in Maine. And she worried about her husband, the poet Robert Lowell. Since age seventeen, Lowell, who was diagnosed with manic depression in the 1940s, had occasionally entered states of high mania, impulsive stretches during which he seduced young women, raged at loved ones, and, once, dangled a friend out a window. For years,

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

Everyone who’s writing essays professionally these days owes a debt to Meghan Daum, whether they know it or not. Her 2001 collection My Misspent Youth paved the way for many people’s careers, including my own. More than any of her contemporaries, Daum staked a claim on the trickier-than-it-looks style that combines journalistic rigor with exactly the right amount of subtle humor. She wrote about getting deep into debt and continuing to buy flowers from the corner bodega. She coined a term for the existential discomfort of aesthetic wrongness: Wall-to-wall carpet, famously, is “mungers.” She described the life of a friend

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

Howard Koch Jr., assistant director on Chinatown and the son of the former head of production at Paramount Pictures, had always thought of cocaine as “elite,” according to Sam Wasson in The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood. But by 1975, coke had trickled down. “The fucking craft service guy had it . . . the prop guy had it. It was everywhere,” Koch Jr. noticed.

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

Across several decades of her career, Helen Frankenthaler painted an intimate, interior sense of landscape. She achieved this, in part, with a technique called “soak stain,” which she invented while creating her earliest masterwork, Mountains and Sea, 1952. Frankenthaler would pour paint diluted with turpentine onto unprimed canvas, creating watercolor-like effects. The softened hues and diffuse shapes captured the subjective experience of the natural world. While watercolors are typically small, Frankenthaler preferred large canvases, sometimes as wide as twelve feet. The scale and the method harked back to J. M. W. Turner’s gauzy Venetian skies and waterways.

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

Lily Dale, a small town in upstate New York—ostensibly frozen in time, with its pretty Victorian buildings, bucolic surroundings, and air of sleepy gentility—was established in 1879 as a sanctuary for practitioners of Spiritualism. This religious movement (which had connections to several reformist and progressive causes of the nineteenth century, including women’s suffrage and abolitionism) posits that the veil separating the living from the deceased is porous, and can be breached by those blessed with special gifts. The burg, which is also home to the National Spiritualist Association of Churches, thrives: As of 2018, there are fifty-two registered mediums who

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

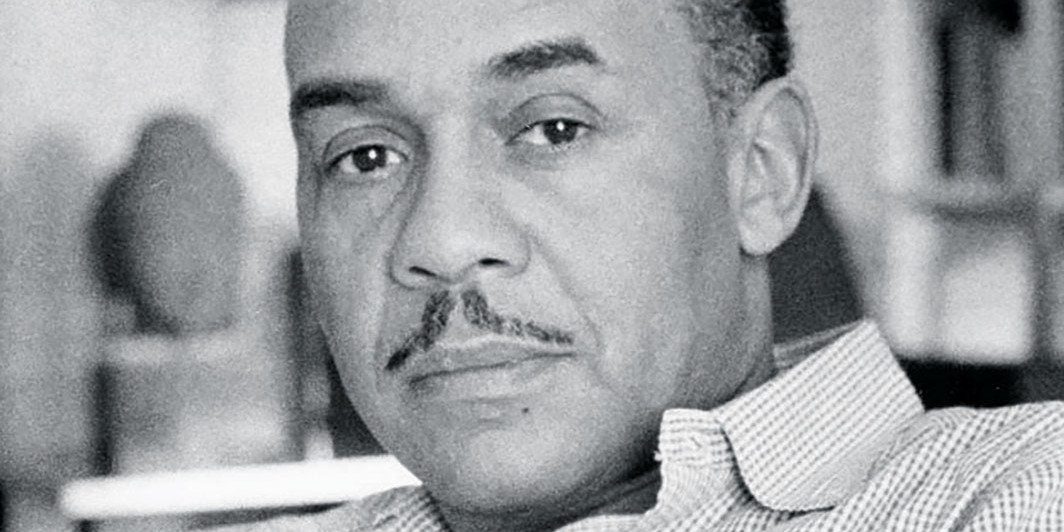

ANY OPPORTUNITY TO READ A GREAT WRITER’S MAIL should be embraced in these days when a serial Instagram feed is about as ambitious as correspondence gets. Granted, at roughly a thousand pages, The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison may be asking a lot, at the outset, of even the most committed scholar of twentieth-century American literature, to say nothing of the waves of readers who continue to come away from Invisible Man convinced that it’s the Great American Novel.

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

As an occupation perceived to be perpetually on the brink of obsolescence, reading has to have one of the most esteemed reputations of any human activity. We are encouraged to think of it as a virtue in itself: Entire cities are urged to simultaneously read the same book; the demise of a single bookstore inspires heartfelt tributes from those inclined to conflate poorly conceived small-business models with intellectual nobility; it is said to bind communities at the same time as it is said to free the mind. Reading has been pondered by writers from Francis Bacon to Maurice Blanchot; the

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

James Wood, haters claim, is a hater. The New Yorker’s most influential and polarizing critic hates gaudy postmodernists like Paul Auster and cute sentimentalists like Nicole Krauss. He can’t stand the Cambridge fixture George Steiner, whom he pillories as “a statue that wishes to be a monument,” and he dismisses Donna Tartt as “children’s literature.” Most famously, he loathes fidgety, frantic novels by the likes of Thomas Pynchon and Zadie Smith, works of so-called “hysterical realism” that can’t shut up and sit still. In 2004, the editors of n+1 denounced him as a “designated hater.”

- review • January 23, 2020

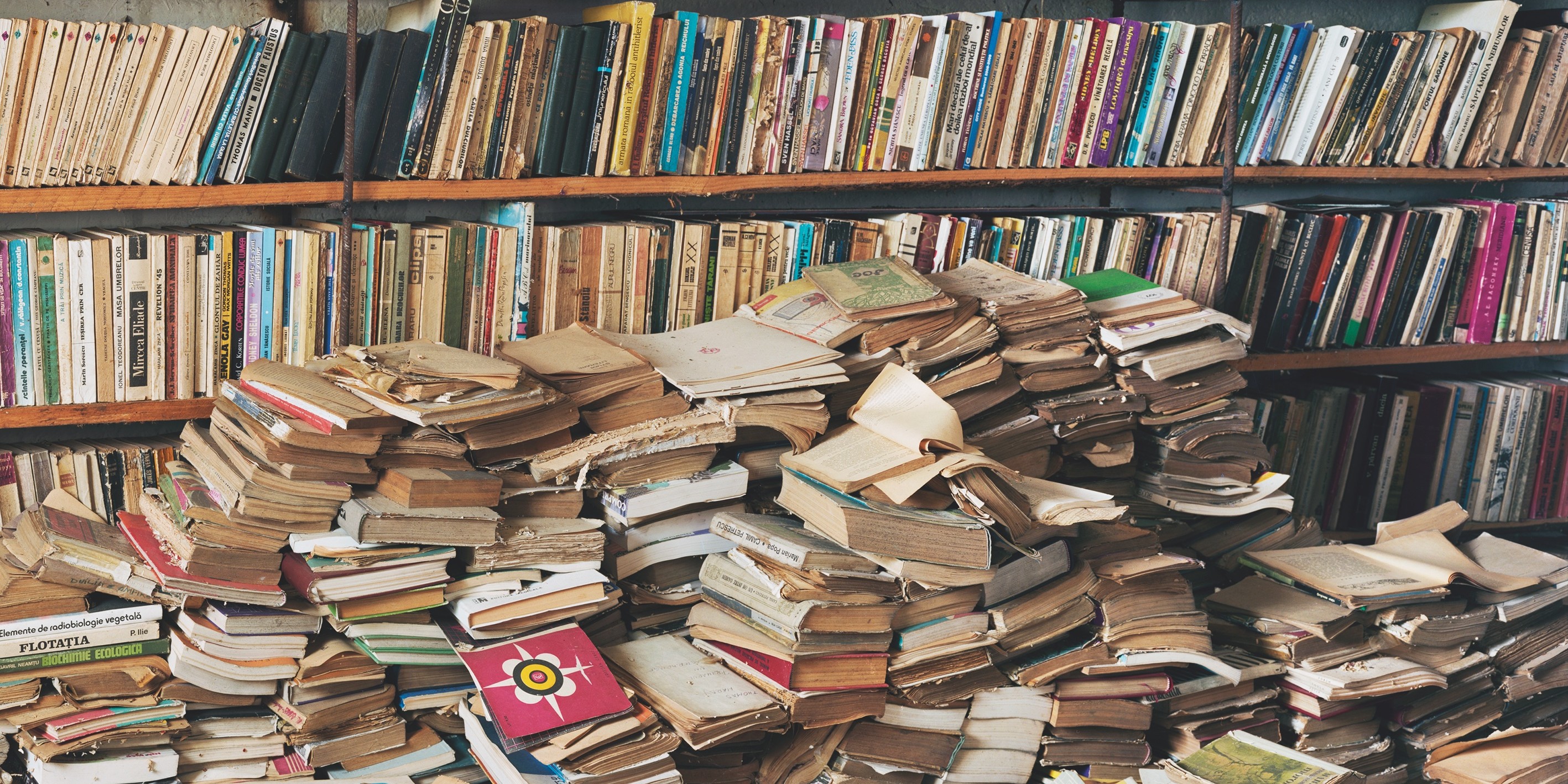

The pivotal moment of the book of Job occurs in its final chapter. Job, the paradigm of piety—God-fearing and evil-shunning, as he’s introduced in the book’s first lines—has, despite his moral uprightness, suffered profoundly. He has endured the deaths of his ten children; an excruciating, all-consuming skin disease; and haranguing by four friends who have insisted, relentlessly, that God wouldn’t torture Job without just cause, despite his repeated insistence that he has done nothing to deserve his fate. In response to Job’s pleas for answers, God himself has spoken to him from a whirlwind. Job’s anguish, the text’s prose frame

- review • January 17, 2020

In Provincetown, a collection of portraits taken in the late 1970s and early ’80s, Joel Meyerowitz captures bodies amber-locked in the beach town’s summer lassitude. The photographer discovered some of his subjects by placing, in the local paper, an ad in search of “REMARKABLE PEOPLE”; others he plucked from crowds with what he calls a “visceral knowing.” Located at the hooked tip of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, Provincetown is buffeted on all sides by the mercurial Atlantic. The town’s reputation as a sanctuary dates back to the seventeenth century, when it was a port for weary Pilgrims on the way to

- print • Feb/Mar 2020

The best pieces of long-form journalism are those where you get the sinking feeling the subject has no idea what the point of journalism is. No inkling that a salacious story is better than a puff piece. No fundamental understanding that a writer, at the end of the day, is only going to make her career if she exploits her subjects, even if it’s just to expose their bad personalities or unkempt apartments. It thrills to read a story that no one wants written about themselves. Whether you are party reporting or writing profiles, you can always find something unethical

- print • Apr/May 2007

Clifford Irving was once a household name. On December 7, 1971, McGraw-Hill Book Company announced the imminent publication of The Autobiography of Howard Hughes, a book Irving had assembled from more than a hundred hours of interviews he’d conducted with the billionaire everyone had heard of but hardly anyone knew. An American expatriate living on the Spanish island of Ibiza, Irving had several thrillers to his name and had recently published a biography of the prolific art forger Elmyr de Hory. Irving, it seemed, sent a copy of that book to Hughes and received in reply a letter scrawled on