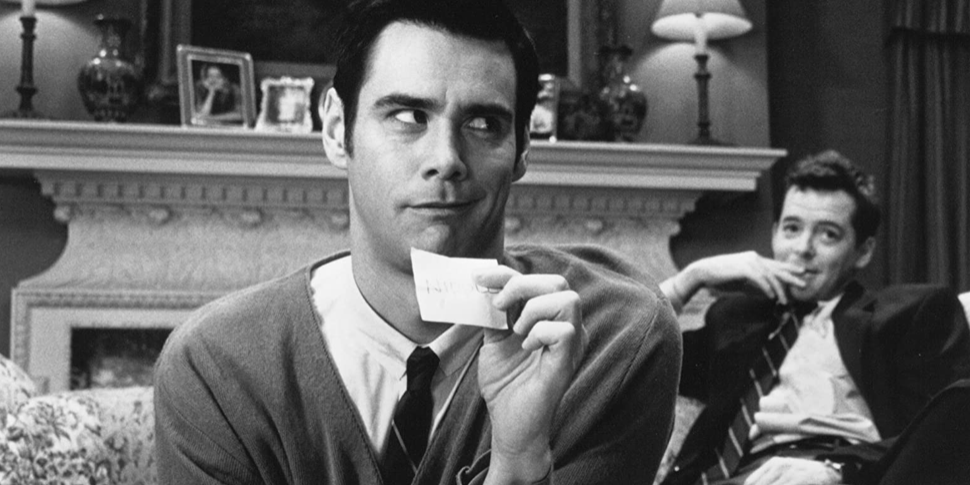

In November 1961, a closeted gay man in a well-tailored suit went to see an unsigned and relatively new musical group performing at a Liverpool club called the Cavern. “I was immediately struck by their music, their beat, and their sense of humor on stage—and . . . when I met them, I was struck again by their personal charm,” Brian Epstein would write in A Cellarful of Noise, his 1964 memoir about the band he would soon manage, make over, and turn into mop-topped superstars. Teasingly, referring to the open secret of Epstein’s private life, John Lennon suggested an

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

PORTIONS OF CLAUDIA RANKINE’S Just Us first appeared in the New York Times Magazine and were posted online with the clickbaity headline “I Wanted to Know What White Men Thought About Their Privilege. So I Asked.” In the article—now the second section of the book, after some introductory poems—Rankine relates some of the material covered in a class called Constructions of Whiteness that she teaches at Yale. As part of the class, her students sometimes interview strangers about race. “Perhaps this is why . . . I wondered what it would mean to ask random white men how they understood

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

TWO FIGURES OVERLOOK A SACRED RIVER: both qualify as students, yet one is more experienced by far. He attempts to bridge the difference with a lesson. Pointing to the wastelands on the right bank, he defines it as sunyata, the void. Then, turning, points at the city opposite. An enormous maze of temples and houses, the dwellings of deities and castes: that is maya, illusion. “Do you know what our task is?” A test. “Our task is to live somewhere in between.” We have two versions of the scene, but in each case the younger student is described as “terrified.”

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

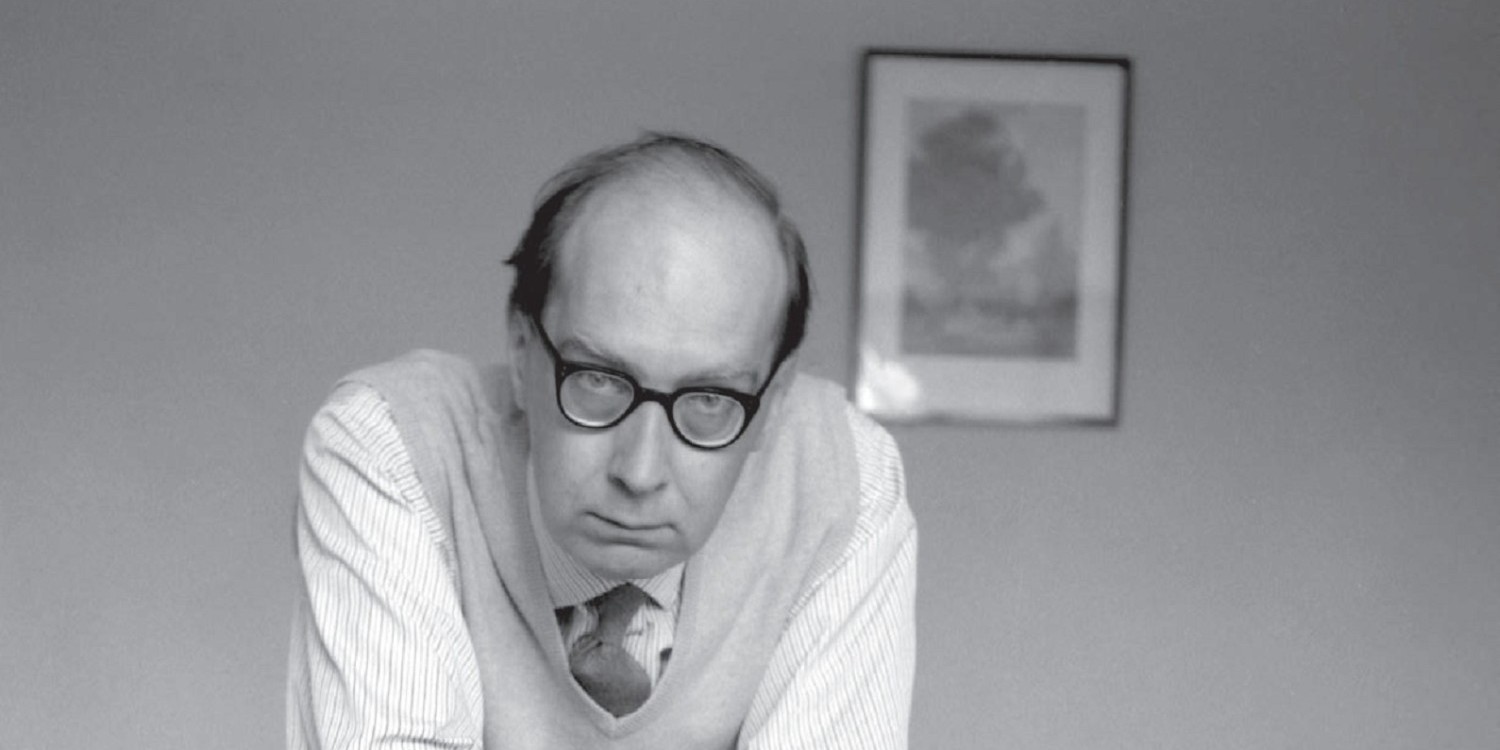

“IT WAS HIS QUOTABILITY,” observed the critic Clive James, “that gave Larkin the biggest cultural impact on the British reading public since Auden.” What comes to mind? The opening lines from “Annus Mirabilis,” certainly—“Sexual intercourse began / In nineteen sixty-three”—but if there is one Philip Larkin quote even better known, it would surely be: “They fuck you up, your mum and dad.”

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

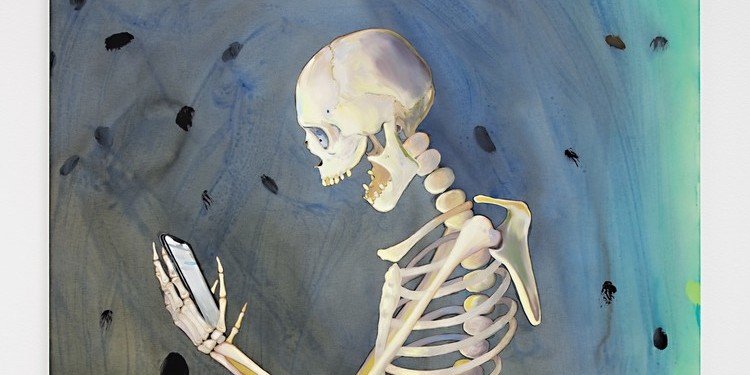

I QUIT TWITTER and Instagram in May, in the same manner I leave parties: abruptly, silently, and much later than would have been healthy. This was several weeks into New York City’s lockdown, and for those of us not employed by institutions deemed essential—hospitals, prisons, meatpacking plants—sociality was now entirely mediated by a handful of tech giants, with no meatspace escape route, and the platforms felt particularly, grimly pathetic. Instagram, cut off from a steady supply of vacations and parties and other covetable experiences, had grown unsettlingly boring, its inhabitants increasingly unkempt and wild-eyed, each one like the sole surviving

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

“A DISAPPOINTED WOMAN should try to construct happiness out of a set of materials within her reach,” William Godwin counseled Mary Wollstonecraft after she tried to kill herself by jumping off a bridge. Virginia Woolf liked to read “with pen & notebook,” a generative relationship to the page. Roland Barthes had a hierarchical system with Latinate designations: “notula was the single word or two quickly recorded in a slim notebook; nota, the later and fuller transcription of this thought onto an index card.” Walter Benjamin urged the keeping of a notebook “as strictly as the authorities keep their register of

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

IN FEBRUARY 2005, the literary theorist Sianne Ngai published Ugly Feelings, a book she described as a “bestiary of affects” filled with the “rats and possums” of the emotional spectrum. Instead of looking to the classical passions of fear and anger, Ngai, then an English professor at Stanford University, wanted to explore what she called “weaker and nastier” emotions. The book is divided into seven chapters, each focusing on a single “ugly feeling” such as envy, anxiety, irritation, and a hybrid of boredom and shock she termed “stuplimity.” Based on Ngai’s graduate dissertation, Ugly Feelings (an unusually laconic title for

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

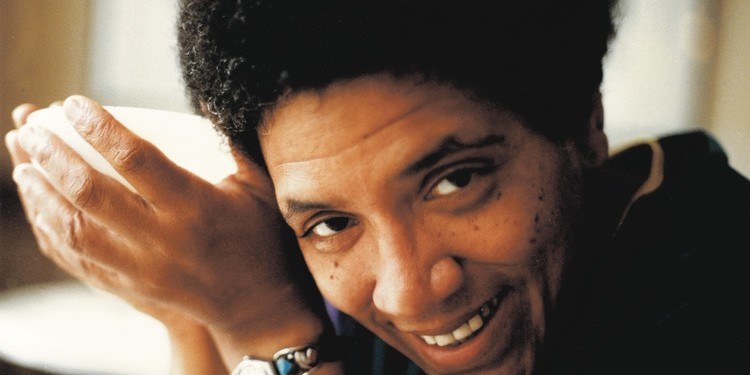

IN AUGUST 1969, the Billboard “Hot Rhythm & Blues Singles” chart was rechristened “Best Selling Soul Singles.” A new type of music had emerged, “the most meaningful development within the broad mass music market within the last decade,” according to the magazine. The genre mystified much of the mainstream press. Publications like Time announced soul music’s birth one year earlier as if it were a phenomenon worthy of both awe and condescension. Its June 1968 issue featured Aretha Franklin as its cover star and called the music “a homely distillation of everybody’s daily portion of pain and joy.” Franklin was

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

WHILE THE BALKANS are generally not known for neighborliness, that reputation is still quite recent. Most would date it to the mid-nineteenth century, when the rise of the nation-state suddenly spurred competition over inheritances that had traditionally been shared. The term “Balkanization”—which crystallized the peninsula’s characterization as bitterly divided—was coined by the New York Times only in 1918, in the wake of the Balkan wars, when the ousting of the Ottomans sparked a land grab among the kingdoms of the former Balkan League. If anything, the previous centuries of occupying empires—from Illyrians and Thracians to Byzantines and Bulgarians—had imparted a

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

As its title suggests, Wagnerism is not precisely a book about Richard Wagner, or even about his music. It is rather, as Alex Ross clarifies, “about a musician’s influence on non-musicians”—a narrow premise seemingly for a work of more than seven hundred pages, but Ross is only teasing out the most salient points from a crowded and mesmerizing history. His book stretches from the opening of Wagner’s first mature operas in the 1840s to the present moment, when fantasy movies and comic books teem with Wagnerian echoes, and the operas themselves are accessible in multiple formats on a previously unimaginable

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

ONE APRIL MORNING in 1973, just before dawn, a ten-year-old Black boy and his stepfather began to run through South Jamaica in Queens. A white policeman had pulled up in a Buick Skylark behind them, the crunch of the car’s wheels on the pavement interrupting the quiet semidarkness. Thinking the mysterious car contained someone who wanted to rob them, Clifford Glover and his stepfather fled. The cop, Thomas Shea, pulled out his pistol and fired into the boy’s back, killing him almost instantly. “Die, you little fuck,” Shea’s partner, Walter Scott, was recorded saying on a radio transmission, though he

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

GIVEN TIME, every discussion of New York in the 1970s becomes a discussion of the South Bronx. When documentary filmmakers need to indicate the decade of New York’s municipal failure, the rubbled lots of the South Bronx mark the moment and do the failing. When overpaid Netflix directors need to gloss the Black experience in New York in the 1970s, an abandoned tenement is cast as the silent buddy. The South Bronx is a real place dogged by the surreal, somehow always most itself when on fire. But New York in the ’70s was not a burning dumpster, and the

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

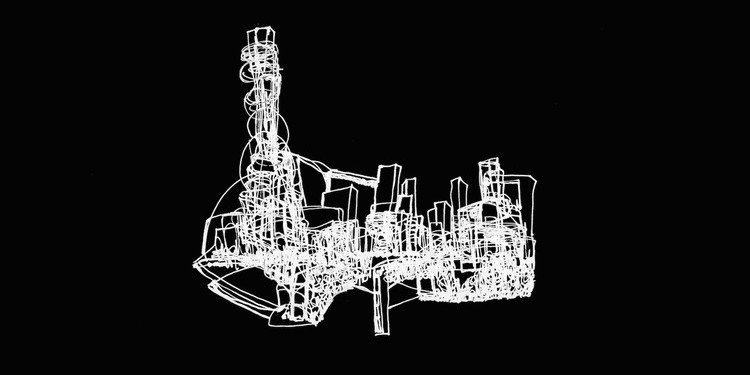

WHEN YOU CROSS the “T” in your signature with a decorative flourish you likely don’t brood on having crossed the boundary separating writing from drawing. That slender gap between visual and linguistic meaning is one explored by poet, essayist, and novelist Renee Gladman. In Prose Architectures, a volume published three years ago, she offered a series of ink drawings that resembled handwriting, architectural blueprints, anatomical illustration, maps, and scribbling while not quite resting within any one of those categories. Her drawings moved energetically between figurative and abstract elements, between the legible and the inscrutable. One Long Black Sentence extends and

- print • Sept/Oct/Nov 2020

JACQUES HENRI LARTIGUE (1894–1986), an artist whose work seems to come from another world but in reality comes from the past century, captured that era’s experience of speediness, of beauty, of carelessness, of fun. Born in fin-de-siècle France, Lartigue started shooting film as a child. Though he thought of himself as a painter first, Lartigue became famous for photographing auto races, early aviation, beachside horseplay, and society women on the Bois de Boulogne. He pioneered techniques for capturing heart-stopping proto-parkour, like a quick dandy jumping over some lazy chairs, or, in My Cousin, Bichonnade, 40 rue Cortambert, Paris, ca. 1905,

- review • July 30, 2020

In 2008, Paul B. Preciado published Testo Junkie, which is, among other things, an influential account of his illegal self-administration of testosterone gel. Stints of heady Foucauldian theory are interspersed with powerful memoiristic passages: He writes elegiacally to a friend who recently died, begins a potent affair with the French feminist writer and filmmaker Virginie Despentes, and lyrically describes the effects of testosterone on his body and mind. With a lofty sense of ritual and menace, he compares the packets of gel to “dissected scarabs, poison bullets extracted from a corpse, fetuses of an unknown species, vampire teeth capable of

- excerpt • July 7, 2020

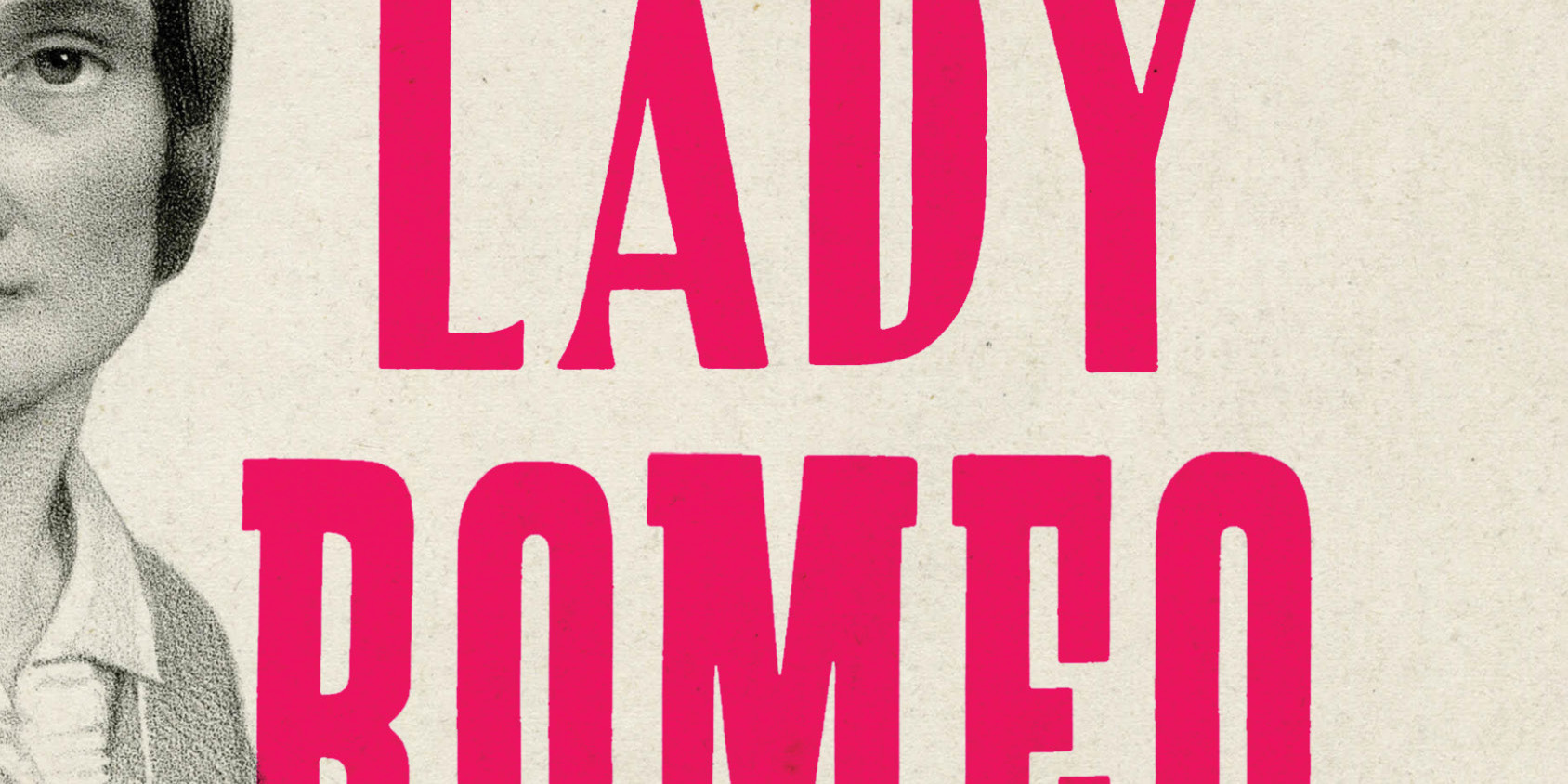

Charlotte Cushman was once called “the greatest living actress.” In the mid-nineteenth century this queer, Shakespearean performer was all the rage. Walt Whitman called her a genius, Louisa May Alcott had a stage-struck fit over her, Lincoln made her promise to perform for him (she did) and she impressed luminaries from Charles Dickens to Henry James. She rose from poverty to become America’s first celebrity, while specializing in ambitious women and transforming how we think of Shakespeare through her male roles like Hamlet and Romeo. After becoming an icon, Cushman lived openly with her female partners, facing off with critics

- review • May 28, 2020

Welcome to part three of our ongoing series about supporting the literary community during the coronavirus pandemic. This week, we focus on independent bookstores and authors in need.

- print • Summer 2020

IN 1974 DORIS LESSING PUBLISHED MEMOIRS OF A SURVIVOR, a postapocalyptic novel narrated by an unnamed woman, almost entirely from inside her ground-floor apartment in an English suburb. In a state of suspended disbelief and detachment, the woman describes the events happening outside her window as society slowly collapses, intermittently dissociating from reality and lapsing into dream states. At first, the basic utilities begin to cut out, then the food supply runs short. Suddenly, rats are everywhere. Roving groups from neighboring areas pass through the yard, ostensibly escaping even worse living conditions and heading somewhere they imagine will be better.

- print • Summer 2020

SØREN KIERKEGAARD WAS AN EARNEST, brilliant, difficult, vituperative, sensitive, sickly emo brat whose statue in the Valhalla of Sad Young Literary Men is surely the size of a Bamiyan Buddha. He was a Christian whose devoutness was so idiosyncratic as to be functionally indistinct from heresy; who lived large on family money until the money ran out and then died so promptly that you’d almost think he planned the photo finish; who tried and failed to save Christianity from itself, but succeeded (without really trying) in founding “a new philosophical style, rooted in the inward drama of being human.” That

- print • Summer 2020

DURING THE FIRST WEEKS of quarantine, I would become exasperated when I’d hear some expression of gratitude for the platforms and technologies keeping us socially connected, as though connection is only virtuous, or would be balm enough. It seemed apparent that the value of disconnection was an equally pressing lesson, a condition put before us to wrestle with, to practice, to sit with, and, perhaps, to learn from. Perhaps disconnection would even be essential to defining how and in what altered state we might arrive at the other side of this horrific, if expected, shakedown. Wanting role models for living