In the United States in the mid-1960s, a case came before the Supreme Court, one intended to settle the question of obscenity addressed by the famous Roth decision of 1957. The nine quarrelsome old men now came to the conclusion that obscenity required a work to be utterly without any redeeming social value. Whammo! There was a thoughtful pause whilst the country digested that—and came to the conclusion that of course there was a revelatory and redeeming social value to even the lousiest suckee-fuckee books. The gates were opened. The flood began. Suddenly all the old four-letter words (and some new ones) appeared in print, almost overnight. Publishers no longer had to write prefatory notes condemning what they were printing; they could merely suggest the social significance of erotica, and lo! all was satisfied. The court’s decision had more holes in it than a colander, and publishing houses sprang up like mushrooms after rain.

In the passage above, pornographer, tattoo artist, and erstwhile literature professor Samuel Steward reflects on a moment whose import for our understanding of gay literary fiction, pornography, and print culture has been largely underappreciated. Steward has in mind the rapid attenuation of US obscenity law at midcentury, when the state’s waning interest in censoring sexually explicit media led to a remarkable change in the kinds of texts available to a general readership. Of course, his account of that transformation is less than precise: the explosion in pornographic writing in the US was the consequence of not one but a string of interrelated Supreme Court decisions delivered between 1957 and 1966, which were themselves the product of numerous courtroom battles stretching back well into the early twentieth century. While Steward fudges the historical details, his account of what those changes meant for publishers, writers, and readers is accurate. The court’s protracted development of a new framework for assessing obscenity not only enabled the rapid proliferation of markets for pornography, which included both homegrown varieties and imports from around the world, but also allowed publishers, and Grove Press in particular, to popularize the texts of the modernist avant-garde, many of which had been banned in the US for pushing the boundaries of sexual propriety in the name of art. In response to the freedoms afforded to publishers and writers by this new legal context, the First Amendment lawyer Charles Rembar triumphantly declared this moment “the end of obscenity” and predicted that the censorship of sexually explicit writing might soon be a thing of the past.

Given the significance that such legal changes had for writers, it’s tempting to follow Rembar in construing the end of obscenity more or less in terms of a progress narrative. However, over the past twenty years, a number of scholars, including Florence Dore, Loren Glass, Elizabeth Ladenson, Alison Pease, and Rachel Potter, have highlighted the extent to in which the interrelated notions of obscenity, pornography, and censorship in fact, not only drove the formation of an elite literary modernism, but also had a key role in its wider dissemination. According to Pease, the aesthetic theory of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries relied on pornography to clarify the specific, and specifically aesthetic, value of literary writing. Where the latter engaged the reader in the disinterested contemplation of beauty, the former turned one’s attention toward the self-interested pleasures of the flesh.

Beyond being a mere description of particular textual properties, the distinction between literature and pornography also served the ideological ends of class differentiation. While perceived as the means by which one expressed one’s elite standing, the ability to produce and recognize texts with distinctly literary value was also understood to be available only to the population of white male property holders largely responsible for articulating such theories of value. In contrast, pornography increasingly described an aesthetically inferior form of writing associated with the popular entertainments of the working classes. Thus, pornography was recognizable, not only in terms of its crudeness, but also in terms of the relations of power that subordinated it to literature as the thinking man’s art.

By the early twentieth century, writers sought to push both aesthetic and social boundaries through the deliberate incorporation of explicit sex into their work. The goal was not to arouse the reader but to bring the aesthetic to bear on the subject’s sexualized interiority: unlike the pornographer who wallowed in filth, literary genius sublimated sex into art. Such literary innovation set the scene for the US obscenity trials of the early twentieth century, which in turn drove the growth of an internationalized professional culture of writers, publishers, and First Amendment lawyers seeking to combat not only censorship but also the unauthorized sale of pirated editions.

By the mid-twentieth century, writers, critics, and academics had successfully popularized the values of social realism, according to which literature should represent life in all its sordid detail, and of literary modernism, which championed “art for art’s sake,” such that they could serve as persuasive arguments for the defense of controversial texts in the nation’s courtrooms. By 1966, the growing acceptance of literature’s capacity to represent human sexuality would lead Steven Marcus to argue that arousal was itself an acceptable response to literature. Moreover, once liberal democratic societies finally came to terms with that fact, then pornography itself would cease to exist: “Pornography is, after all, nothing more than a representation of the fantasies of infantile sexual life,” Marcus observed in the conclusion to his study of Victorian pornography. “Every man who grows up must pass through a phase of his existence, and I can see no reason for supposing that our society, in the history of its own life, should not have to pass through such a phase as well.”

Of course, Marcus’s prediction did not come true, and scholars have explained why by offering detailed accounts of the history of that moment. However, we know far less about what happened after, when “pornography” was no longer simply the slur of “aesthetic immaturity” that forewarned an obscenity charge but increasingly referred to a genre of representation and a semi-legitimate niche market for specific populations of readers. In continuing to neglect these materials, scholars risk tracking too closely with the law, losing interest in pornographic writing when, as Pease declares, “specific and overt references to sex acts and sexualized bodies [are] so much a part of literature, including works of high-cultural aesthetic status, that today they hardly seem worth notice.” For Steward, the end of obscenity was not so much an ending but a beginning, something worth noticing, especially for the many gay men who were becoming increasingly conscious of themselves as members of a distinct minority by reading the books that writers like Steward were beginning to publish. His account of that change is also suggestive: the mycological metaphor he employs prevents him from falling easily into the kind of straightforward narrative of de-repression favored by writers such as Rembar and Marcus. Instead of unrestricted speech, there is a sense of something changed by the wash of four-letter words and the clusters of smut peddlers that sprouted up across the nation’s publishing landscape. Within the new cultural ecology that Steward imagines, the meaning and import of all those four-letter words is far from clear.

The attenuation of federal obscenity law established the conditions for gay pornographic writing and gay literary fiction to emerge in relation to one another; thus, any attempt to understand contemporary gay literary production must do so through an understanding of its fundamental connection to the genre of gay pornographic writing. Contemporary literary studies tend to ignore this relation, thereby preserving an erroneous assumption that gay pornographic writing was an immature form of culture whose popularity inhibited the commercial and critical success of gay literary fiction. While it’s unlikely that anyone would make that argument in precisely those terms today, its implicit force is still palpable, especially in studies of gay print culture that construe pornographic writing published after 1970 as little more than a private, masturbatory pleasure. Even the field of porn studies, which has done more than any other field to describe pornography’s social and political significance, has by and large neglected to account for pornographic writing published in the contemporary period. Owing to the ways in which that field that took shape within film and media studies departments during the 1980s, contemporary pornography has become more or less synonymous with the pornographic image, while pornographic writing becomes a quaint relic from the pre-Stonewall era.

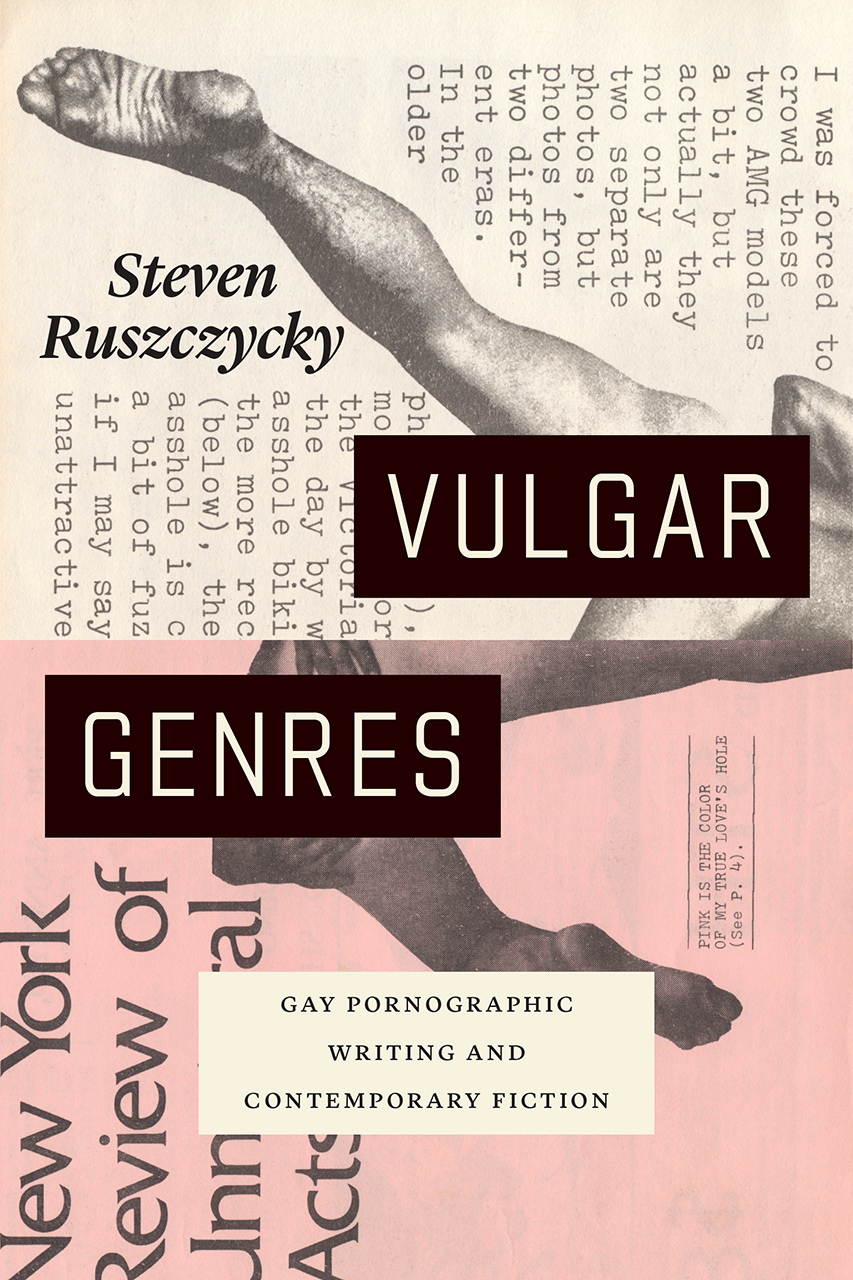

Reprinted with permission from Vulgar Genres: Gay Pornographic Writing and Contemporary Fiction by Steven Ruszczycky, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2021 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.