Justin Taylor

WHEN A NOVELIST’S sophomore novel is narrated by a novelist bemoaning the New York Times review of her first novel, even the most auto-skeptical critic might be forgiven for pulling up a search window. Turns out that the Times review of Lexi Freiman’s Inappropriation (2018) is nothing like the “cancellation” her character, Anna, undergoes in The Book of Ayn. However, the review does begin by declaring that “Satire is a difficult genre to neatly define,” followed immediately by a definition that is roughly what you’d get by googling “satire definition.” You can hardly blame Freiman if reading these words in

“IT MAY BE THAT THE subconscious is really a committee,” Cormac McCarthy tells Oprah in their 2007 interview, a full eight years before he could have gotten the idea from Disney-Pixar’s Inside Out. “They may have meetings and say, ‘What do you think we should tell him? Should we tell him that? Nah, he’s not ready for that.’ . . . Sometimes the sense of the subconscious and its role in your life is just something you can’t ignore. It may have to do with the subconscious being older than language, and maybe it’s more comfortable creating little dramas than

A SPECTER IS HAUNTING AUTOFICTION. The specter of ripping off your life for your novel and not making a whole goddamn thing about it. Elizabeth Hardwick’s unnamed narrator spent her Sleepless Nights in Elizabeth Hardwick’s apartment and it worked out fine for both of them. Roth had Zuckerman and, later, “Roth,” and later still Lisa Halliday had “Ezra Blazer.” There have been abundant Dennises Cooper, Joshuas Cohen, and Dianes Williams. Sebald and Bellow—just saying the names should be enough. Jamaica Kincaid gave Lucy her own birthday. Then you’ve got the New Narrative movement of the ’70s and ’80s, plus a

I DROVE ACROSS the Everglades in May. I had originally planned to take Alligator Alley, but someone tipped me off that, in the twenty years since I left South Florida, the historically wild and lonesome stretch of road had been fully incorporated into I-75, turned into a standard highway corridor with tall concrete walls on both sides, designed to keep the traffic noise in and the alligators out. So on the drive west from Boynton Beach, I took the northern route, skirting along the bottom of Lake Okeechobee (which you can’t see from the road) through new subdivisions and past

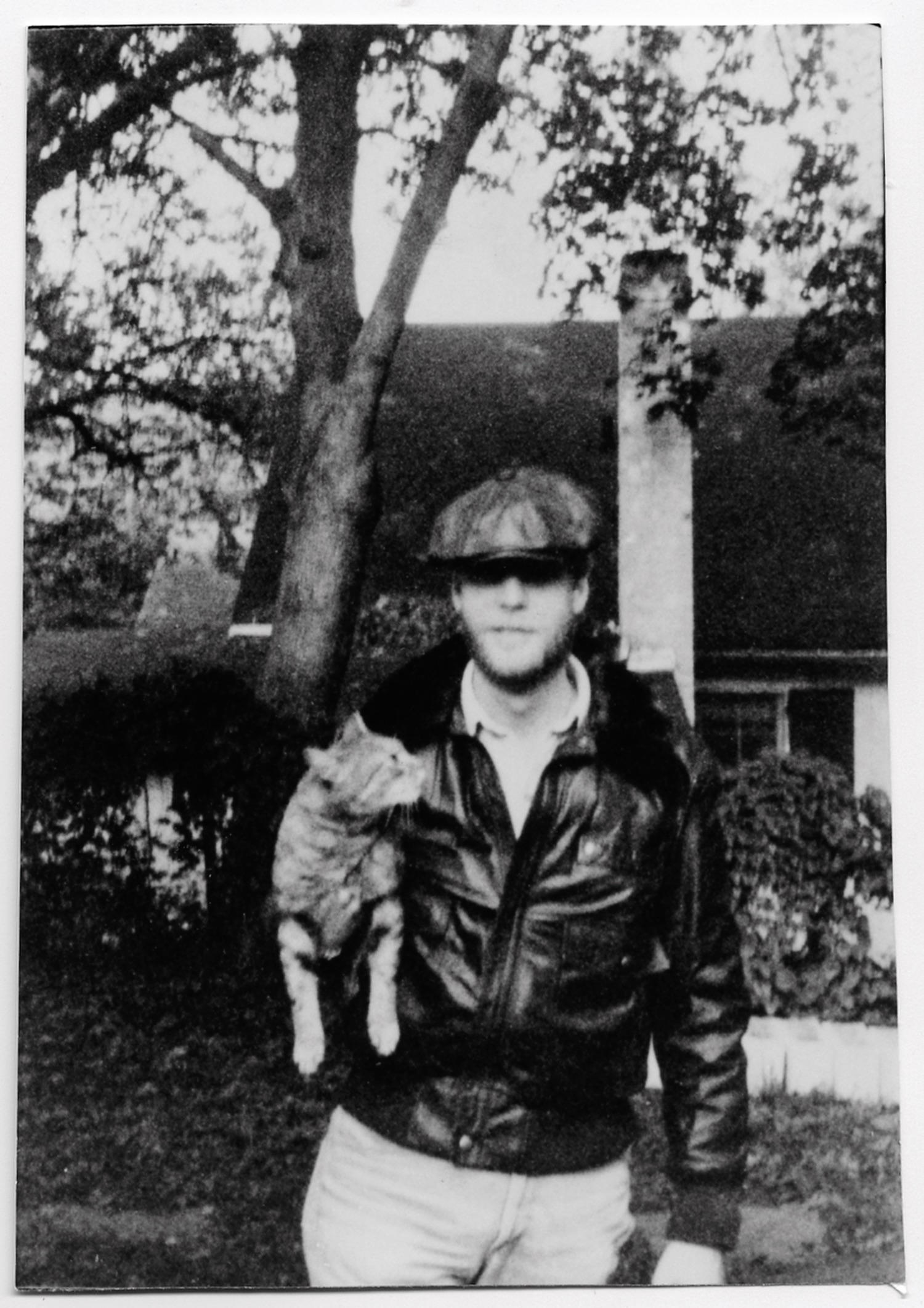

IN 1975, BREECE D’J PANCAKE was a twenty-three-year-old English teacher at Staunton Military Academy in the Shenandoah Valley. He was half a day’s drive from Milton, West Virginia, where he’d grown up. He hated the brutal, stultifying culture of the school, but the job was enough to support himself as long as he lived cheaply, which was important because his father had multiple sclerosis and could no longer work. His parents, Helen and C. R., said they were getting by, but he worried about their long-term financial security. Pancake was a loner, a dreamer, a contrarian, a depressive—in short, a

SØREN KIERKEGAARD WAS AN EARNEST, brilliant, difficult, vituperative, sensitive, sickly emo brat whose statue in the Valhalla of Sad Young Literary Men is surely the size of a Bamiyan Buddha. He was a Christian whose devoutness was so idiosyncratic as to be functionally indistinct from heresy; who lived large on family money until the money ran out and then died so promptly that you’d almost think he planned the photo finish; who tried and failed to save Christianity from itself, but succeeded (without really trying) in founding “a new philosophical style, rooted in the inward drama of being human.” That

Please don’t bury me Down in that cold, cold ground No, I’d rather have ’em cut me up And pass me all around —John Prine, “Please Don’t Bury Me” Fearful indeed the suspicion—but more fearful the doom! It may be asserted, without hesitation, that no event is so terribly well adapted to inspire the supremeness of bodily and of mental distress, as is burial before death. —Edgar Allan Poe, “The Premature Burial” There could be unexpected chiming or clanging. —Lorrie Moore, “Author’s Note” to Collected Stories IF THE STRANGEST THING ABOUT LORRIE MOORE’S COLLECTED STORIES is that it didn’t exist

“I do not believe in serendipity,” says Percy, the narrator of Jessi Jezewska Stevens’s The Exhibition of Persephone Q. “I don’t think there are moments, of which so many people speak, in which a life irrevocably and neatly forks, like a line in your palm. I believe instead that the past returns to you in waves, crashing onto the shore, so that the ground on which you stand is always shifting, like a beach, imperceptibly renewed.” I found myself returning to this passage throughout my reading, and for some days afterward, trying to decide whether I believed it, either as

I know it’s not a popular opinion, but I’ve always felt that Saul Bellow did some of his finest work in the short story. They’re almost all novella-length, but even so, the limit imposed by the form provides a propitious counterforce to Bellow’s natural maximalism, and the results feel simultaneously epic and economical. I readily rank his Collected Stories up there with Herzog and Augie March at the apex of the Bellow canon—assuming, which I suppose I shouldn’t, that such a thing still exists. Moreover, Bellow’s stories often find him mining his early, formative experiences as the child of Lithuanian “Memory,” says Plotinus, “is for those who have forgotten.” The gods have no memory because they know no time, have no need to fight against time, have no fragments of what has been lost to recollect, to re-collect. In India, with its vast stretches of time, with its same lives appearing and appearing again, there is no distinction between learning and remembering. You knew it in your past lives, you have always known it, to learn is to re-mind yourself, bring yourself back into the mind of universal knowledge. Says the Jaiminiya Upanishad: “It is the unknown that you should